From the first rule to the statutes’ official approval by the Catholic Church in 1990

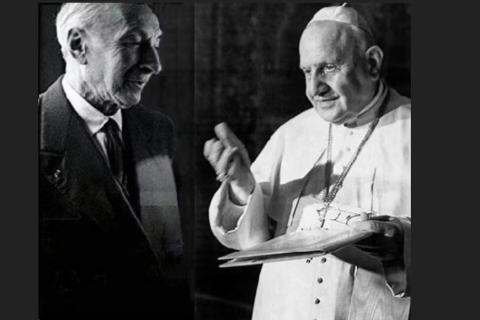

Photo courtesy of Citta Nuova

Is the plan of God on this Movement complete? Does its position only have to be consolidated, or will something new still happen? Experience leads me to believe that we will see something new.”

Chiara Lubich wrote those words in 1977. Those who had had the privilege of working with her on that masterpiece that the General Statutes of the Focolare Movement represent, were left with the impression of having somehow touched her relationship with the Holy Spirit, who was “dictating” to her new words with which to describe the Work of Mary.

She would review the statutes text article by article, saying for example, “This can be included … this one doesn’t seem part of our charism.”

The history of the Focolare is defined by two inseparable realities. One is universality, the aspiration to unity that God placed in the movement, giving it an outward, diffusive thrust that reaches the ends of the earth. The other is something typical of human institutions, which limits the spiritual reality to historical events connected to well-determined persons and things.

Right from the beginning, the Church understood that this community of Christians had its roots in the Gospel and from there it found the way to apply it to life situations. It was the seed of a new little plant.

The first rule

The first request for a written statute came from the Bishop of Trent, Carlo de Ferrari. Chiara responded by compiling and submitting the “Statute of the Focolare of Charity,” with the subtitle “The Apostles of Unity.”

In embryonic form, it contained the future developments and the newness, freshness and universality of the experience that was happening. It was approved on May 1, 1947 for the Diocese of Trent and, after a trial year, it was renewed for an additional three years.

Meeting Igino Giordani in 1948 and Pasquale Foresi at the end of 1949 added new components, as well as the challenge of finding acceptable juridical wording to express the reality that was coming to life.

The presence of married members appeared essential to the Focolare, and the priestly vocation felt by some focolarini, previously only laypeople, clarified that they would be characterized by a special affinity with the priesthood of Christ, which in some of them would become a ministerial priesthood.

Waiting on the approval

However, it was not yet time to be approved by the Church. There was an intense period of work on different compositions of the rules, and still no official word. It was for Chiara a time of suffering, because the encounter between the charismatic aspect and the juridical one was not emerging definitively.

The Supreme Congregation of the Holy Office studied the movement from 1948 to 1957.

In the statute of 1954, the charism stood out clearly, the fulfillment of Jesus’ prayer “Father, that all may be one.” Many, however, who were already living the spirituality, were not included.

They were included in the draft written in 1958, where the movement appeared composed of an “order” (single and married focolarini), a “league” that embraced diocesan and religious order priests and a lay movement.

In 1959 a Jesuit priest, Giacomo Martegani, intervened in the writing of the fifth rule. In 1960 the movement was entrusted to a group of bishops named by the Italian Bishops’ Conference and a request was made for a sixth rule: a “compendium of some fundamental norms for the future constitution of the Secular Men’s Institute ‘Work of Mary’ and the Secular Women’s Institute ‘Work of Mary.’”

Separate and aggregates

“God was leading the Church and illuminated it so that we would not be left in abandonment. He had been the founder and architect of the wonderful work that was coming to life. He had nourished it with his Spirit, and it was formed by him alone,” Chiara wrote in The Cry.

Helped by some of the more mature men and women focolarini, and with the fundamental contribution of Pasquale Foresi and Igino Giordani, Chiara rewrote and presented two separate statutes, one for the men focolarini and one for the women focolarine, as the Church had asked.

These, however, envisaged only the consecrated members. All the other vocations of the Work of Mary that had emerged up until then were included as “aggregates” of the focolarini or the focolarine

In search of a connecting element

Finally, a few months before the opening of the Second Vatican Council on March 23, 1962, the long-awaited approval arrived from Pope John XXIII of the statute of the men focolarini ad experimentum, that is, on an experimental basis. The following year a similar, almost identical approval arrived for the women focolarine

“For us,” Chiara would later write, “a new moment, mixed with light and touches of shadow, is beginning.” The approval signaled joy, although a doubt and a suffering remained, because the two separate rules seemed to compromise the unity of the one movement born from a single charism.

Pope Paul VI proposed studying a way to keep the two sections of the Focolare united. And a trait-d’union, a “connecting element” was found: a coordinating council would be the expression of the unity of the Focolare when it came to shared events.

On January 26, 1966, the Congregation of the Council approved the statute. For Chiara and those in leadership positions, although aware that there was still work to be done for the revision of the three statutes, the approval gave the certainty that the Church already recognized the Work of Mary as an offshoot of its own stock.

Winds of change

The climate of Vatican II generated innovations in the organization of the Church. A communication that came from Cardinal Wright on December 21, 1978, stated that, according to a decision of Pope John Paul II, the Focolare Movement would pass from the Sacred Congregation of the Clergy to the Pontifical Council for the Laity

In the meantime, the new Code of Canon Law was promulgated. Cardinal Opilio Rossi, president of the new council, suggested to Chiara to work once again on the statutes and describe the actual situation of the life and the structure of the Work of Mary.

It would take time and would need to also include the results of the ecumenical, interfaith dialogues and the dialogue with people who have non-religious convictions. People from all these groups were by now part of the movement. Lengthy consultations began with members of the Pontifical Council for the Laity and seasoned canon lawyers.

The stamp of approval

Joy resounded when in 1990 Chiara received the decree of approval from the hands of Cardinal Eduardo Pironio. Finally, this juridical composition had become “the chalice wherein it was now possible to decant the charism received from God.”

Everyone in the movement was in some way represented. The moment had arrived to underscore the prophetic grace of a charism in the Church, attune to the Holy Spirit that wants to align norms and life.

The General Statutes of the Work of Mary present the Focolare Movement as an “association of the faithful,” a rich and diverse people ordered in sections (men focolarini and women focolarine), branches, movements, all oriented toward one goal: unity.

“Many times in these days it came to me,” Chiara later wrote, “that if I were to die I would take with me into the next life the great joy of having contributed to a work of God, which since it is Church, will remain after me.”