Kierkegaard viewed life as a dialectical progression in which we pass through different stages, but he also uses the term “existence-spheres.” The first is the esthetic; secondly, there is the ethical; and finally you have the religious dimension.

Photo by wikipedia.org

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (1813–1855) spent most of his life in Copenhagen, Denmark, and only travelled on a few occasions to Berlin and Sweden. His interests and writings cover a wide area, including philosophy, theology, psychology, literary criticism, religious literature and fiction.

He used amusing pseudonyms in some of his writings, like Anti-Climacus, Father Taciturnus, Johannes De Silentio and Hilarius Bookbinder. This was not just a sign of a certain quirkiness; rather, his indirect method encouraged readers to really participate in Kierkegaard’s reflective journeys and take on personal responsibility.

As he wrote in Either/Or, he felt that “as soon as a person can be brought to stand at the crossroads in such a way that there is no way out for him except to choose, he will choose the right thing.”

Kierkegaard saw the fundamental challenge in life as not in “what am I to know,” but “what am I to do.” He says in his Journals, “The thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live or die.”

He asks, for instance, what good is it being able to explain the meaning of Christianity if at the same time it has “no deeper significance for me and for my life.” The imperative, he argued, is in living and not just understanding. Indeed, he describes how his soul ached for this “as the African desert thirsts for water.”

At a walking trail in Gilbjerg Hoved, Denmark, there stands a memorial stone to Kierkegaard. In this beautiful area he often enjoyed sitting and being inspired by the whole landscape.

In one journal entry for July 29, 1835, he notes how “the birds sang their evening prayer… I felt so content in their midst, I rested in their embrace… and I turned back with a heavy heart to mix in the busy world, yet without forgetting such blessed moments…”

He says, “[I] saw everything as a whole and was strengthened to understand things differently, to admit how often I had blundered, and to forgive others… I stood there alone… and the power of the sea reminded me of my own nothingness, and on the other hand the sure flight of the birds recalled the words spoken by Christ: Not a sparrow shall fall to the ground without your Father: then all at once I felt how great and how small I was…”

Stages on life’s way

Kierkegaard viewed life as a dialectical progression in which we pass through different stages, but he also uses the term “existence-spheres.” The first is the esthetic; secondly, there is the ethical; and finally you have the religious dimension.

He explains, for example, in Stages on Life’s Way how “there is no human being who exists metaphysically.” In saying this he was not denying the importance of studying the nature [of] reality beyond what we can only see.

But he argued that when “being” exists, “it does so in the esthetic, in the ethical… [and] the religious.” He outlined how “the aesthetic is the sphere of immediacy, the ethical the sphere of requirement… the religious the sphere of fulfillment.”

Each stage is characterized by different experiences, which are all part of the unfolding of who we are as human persons. In the aesthetic we remain just immersed in sensuous experience in which we may end up valuing possibilities over reality and, so, remain closed in on ourselves. In the ethical dimension we act according to social norms.

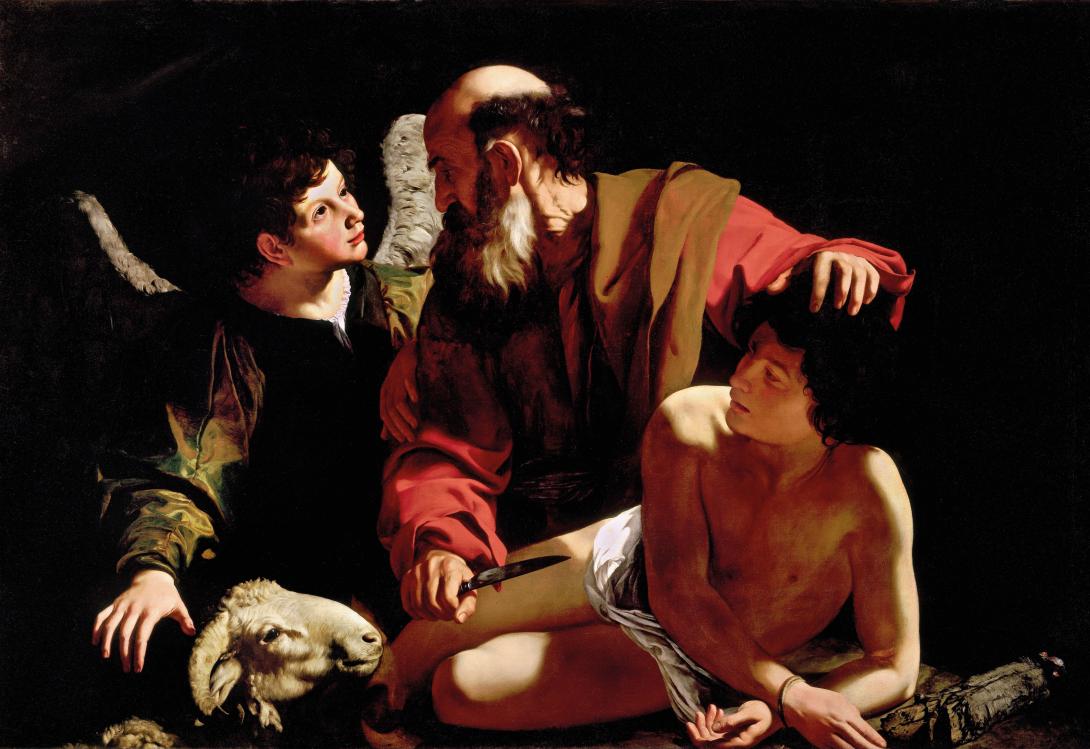

But as we know there are duties and responsibilities which are motivated by truths which lie far beyond what may be considered as societal mores. In Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard gives the example of Abraham’s action in the potential sacrifice of his son Isaac. In fact, there is need, he says, of a “new category for understanding Abraham” and his actions.

“How did Abraham exist?” Kierkegaard asks. [Abraham, he says] had faith. That is the paradox that keeps him at the extremity… for the paradox is that he puts himself as the single individual in an absolute relation to the absolute… if he is the paradox it is not by virtue of being anything universal, but of being the particular.”

The story of Abraham and his son in the land of Moriah (Gen 22) is, according to Kierkegaard, either that of a murderer or else we are moved by “the paradox which is higher than all meditation.”

Abraham is a “knight of faith” because we discover in him how the single individual becomes higher than the universal. In Abraham’s acts there is a going beyond the “ethical,” that is, actions merely measured by societal norms.

So, the “ethical” is also a passageway to the “transcendent,” and the strange thing is that whoever walks on the “narrow path of faith,” like Abraham, cannot be advised or even necessarily understood. Faith, is therefore, “a marvel, and yet no human being is excluded from it.”

In Kierkegaard’s perspective there is a hidden key whereby we can reach towards the “eternal” and so unfold the religious sphere of our existence. In Works of Love, he sees the “neighbor” as the narrow pass giving us access to the “transcendent.” The neighbor is “what philosophers would call the other, that by which the selfishness in self-love is to be tested.”

Kierkegaard explains how “in being king, beggar, scholar, rich man, poor man, male, female, etc., we do not resemble each other—therein we are all different. But in being a neighbor we are all unconditionally like each other… [the] neighbor is eternity’s mark—on every man.”

Kierkegaard observes how you can see the “same watermark” in each one of us. It is through the neighbor that the “light of the eternal shines” through.

The way of Mary

When it comes to understanding the Virgin Mary, Kierkegaard offers some beautiful insights. His emphasis is on how Mary lived as a person.

Mary is properly revered, he says, for saying “yes” and making the choice of God at the Annunciation. Indeed, artists throughout the centuries have rightly depicted this singular event.

Nonetheless, the beauty and depth of who Mary is cannot be contained in writings or works of art. Kierkegaard feels that what is often forgotten is “the distress, the fear… [and] the paradox” she lived through. Her “yes” cost her. She willingly paid for it in living her life as she did.

So, the aesthetic cannot contain her, neither can only describing how she was the “highest” and “purest” of our race. Mary and Joseph, we are told, went down to Bethlehem for the census (Lk 2:1).

They lived within the realities of the required norms (ethical stage). But as we know Mary’s life speaks of the reality of the “beyond” already here on earth amongst us.

All of this, according to Kierkegaard, is fundamental in understanding the way of Mary. The angel who “was not an obliging one… came only to Mary, and no one could understand her.” She is not “at all the fine lady sitting in her finery.”

Kierkegaard reflects on how “she needs no worldly admiration, as little as Abraham needs our tears… both of them became greater than that, not by any means by being relieved of the distress, the agony and the paradox, but because of these.”

Indeed, Chiara Lubich describes how Mary is the “Desolate” one. Mary lived her own “night of the senses,” as for example, in the loss of Jesus in the Temple.

Chiara explains in her Essential Writings how Mary “could no longer see him nor hear his voice; his presence was removed from her motherly love.”

In his Journals, Kierkegaard explains how “just as Christ cried out: my God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me—in the same way the Virgin Mary had to suffer something that humanly corresponded to it.

He observes how “a sword shall pierce through thy own soul—and reveal… that you are in truth the chosen among women, she who found grace in the sight of God.”

So, we can see Kierkegaard had a beautiful intuition into understanding that “being Mary” means embracing everything negative that we might pass through in the stages of life.

In living the paradox of faith as Mary lived, we too can transform it “into love.”