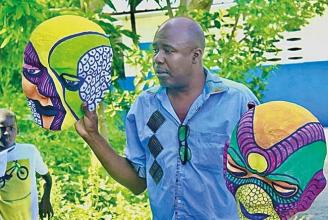

Photo by Childsplay International

Play is essential to culture. As children interpret traditional art forms—painting, for example, or dance, or elaborately constructed masks—they preserve culture, even while they enliven it. They play off a culture’s endless possibilities to stimulate fantasy and imagination.

In the summer of 2022, Childsplay International (CPI) (www.childsplayintl.org) returned to Haiti after an earlier pre-pandemic initiative.

Haiti is achingly poor. It has endured earthquakes and hurricanes. Children have lost parents to HIV. They are often homeless.

But by supporting children’s access to mask-making—Haiti’s quintessential, traditional art form—CPI helped them have fun, and bond over learning an art form with real cultural resonance.

CPI worked with Didier Civil, a widely exhibited master mask-maker eager to pass on his skills. We provided funds (for paint and brushes) and logistical support.

The objective was to help children recover a sense of normalcy despite the natural disasters and chronic poverty. In Haiti, mask-making is basic to the public celebration of Carnival (a sort of institutionalized form of play and of community building).

This is due in part to the importance of voodoo, where masks can represent demons and the dead. Voodoo permeates civic life, in tandem with Catholicism.

Because of our association with Didier, we worked initially out of Jacmel, a small city nicknamed “City of Artists.” The colors are intense. Every inhabitant—all 40,000 it seems—pays attention to costumes and the making of masks.

Papier mâché—the mask-maker’s medium—is simple: mainly newspapers and glue (cheap, accessible materials even in a poor country like Haiti). The materials were right there. You could boil up discarded paper with home-made glue and… voila, papier mâché!

For the workshops, Didier’s helpers prepared the paint and paper, as well as Masonite boards that provided a surface on which the children could work. Everything felt makeshift—as everything in Haiti does—but it was also organized, indicating Didier’s professionalism. Local schools provided space.

Yet while we conceived the activities as “workshops,” the children called them clubs. These all-day gatherings were (in their minds) little communities, where they worked and ate together. So, the collective meals were important—home-cooked, healthy food, consumed as if enacting the children’s mutual respect for each other’s dedication.

The mask-making involved a two-way, participatory process where each child put strips of plaster on the other’s face, then laid gauze on top of that. There was an element of trust, since one’s entire face was covered—you could only breathe by means of straws in your nose that had to be inserted correctly.

This summer, about 200 children attended, aged about 6 to 15. They paid attention. When Didier provided sometimes complicated instructions, the older children helped the younger ones (creating a sort of natural family ecosystem) until everyone could proceed on their own.

When children are given materials and understand how to use them, they will focus. They will play energetically, deliberately, and without further direction. Their natural desire to create kicks in.

The children’s masks represented fantasy creatures and imaginary faces. But they also made masks of individual faces. A child could recreate their own image (however fantastically) in the mask. They could watch themselves create themselves as they might like to be.

The experience was hugely affirmative. In acquiring a skill embedded in their culture, the children enhanced their sense of what they could achieve.

But there was more. Laurencia, an 11-year-old girl, thanked “all these people who supported us.” Suddenly, these children felt relevant.

They learned that one of the best ways to face trauma is to become engaged in meaningful effort with others—including play.

After the workshops, everyone received a certificate of completion. Twenty children, who displayed exceptional talent, were chosen to teach still more children.

But all the children said they felt proud (an uncommon feeling for these children).

Laurencia, one of twenty children chosen for more intensive training, said she felt “honored.” Many masks will be exhibited locally, and some may travel abroad. The initiative is still evolving.