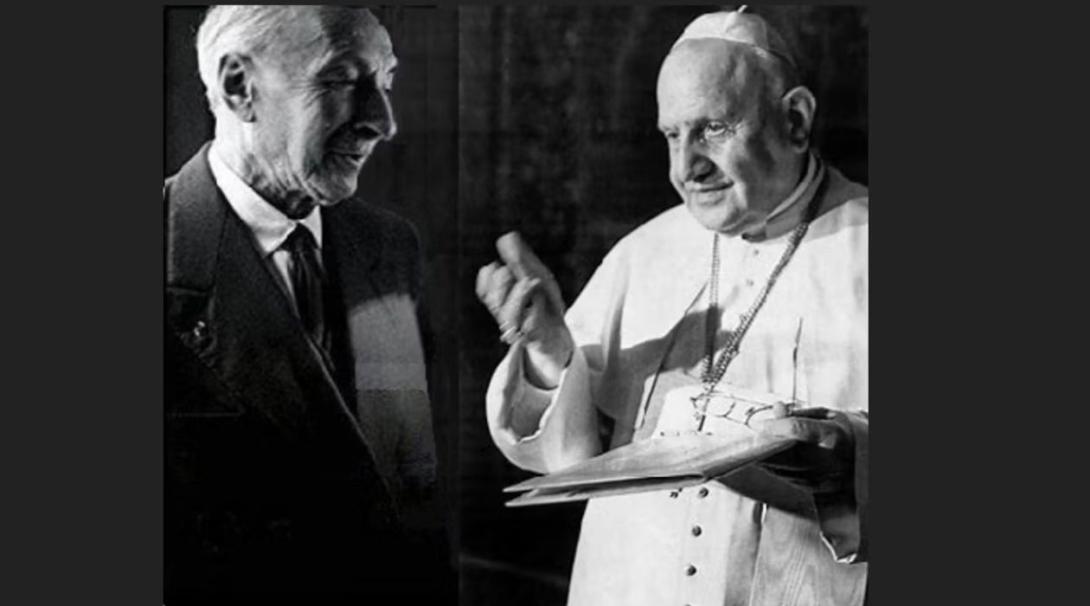

Pope John XXIII and Jewish historian Jules Isaac

The promulgation of the document known as Nostra Aetate on October 28, 1965 was the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the relations between Catholics and Jews. Sixty years later, that history is a very delicate moment which cannot be understood without remembering the previous chapters.

In the early post-World War II period, the issue of the responsibility of Christians for the persecution of Jews was particularly sensitive for Catholics in light of the institutional dimension and centralized structures of the Church: the initial endorsement of Fascism and Nazism by many Catholic leaders; the role of the papacy and the Vatican diplomatic service during dictatorships in Italy and Germany; and the emerging, delicate issue of the relationship with the newly created (1948) State of Israel neighboring with Arab countries where a significant minority of Eastern Catholics lived in a precarious political situation, protected by regimes in relationships far from peaceful with the Jewish state.

These reasons were among the most important for the fact that the agenda of the Second Vatican Council initially did not have in mind a document on the Jews. After the war there had been discussions about the significance of the Holocaust for theology, but they hadn’t affected Rome and the Vatican. One clear sign of change took place in March 1959, when, a few weeks after the announcement of the Council, John XXIII decided to change the prayer for the Jews during the liturgy of Good Friday, with the abolition of the disparaging word “perfidis” (“faithless”) and phrase “iudaicam perfidiam” (“Jewish faithlessness”). It was the first episode of the tumultuous history of the change of Catholic teaching on the Jews.

The decisive moment was June 13, 1960 ,when John XXIII had an audience with the French historian Jules Isaac, who had lost most of his family in German extermination camps and had published the book, Jésus et Israël (1948). Jules Isaac explained to the Pope what he called the common Christian “teaching of contempt” against the Jews. He recommended that he institute a commission to study it.

John XXIII had a particular sensibility to the relations with the Jews, thanks to his experience as a papal diplomat in Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, and France. While in Turkey he met several times with the Grand Rabbi of Istanbul, Markus, and representatives of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and he worked to save the lives of many refugees from eastern Europe: Jews, but also Polish and Greek political refugees. So in September 1960 John XXIII asked the newly created Secretariat for Christian Unity, led by Cardinal Augustin Bea, to prepare the draft of a document on the Jews.

The relationship between 21st-century Catholicism and modern Judaism has become a test for the state of the world and indicative of the chance of healing of the one human family.

Conciliar Debate

Theological, ecclesiastical, and political considerations intersected in the conciliar discussion at Vatican II. An important moment was when the statement on the Jews was taken off the agenda after the news that the World Jewish Congress had appointed (in June 1962) its own “unofficial observer” at the council. Secretary of State Cardinal Cicognani removed the document from the agenda. But in December 1962, at Cardinal Bea’s request, John XXIII put it back on.

Other complicating factors in this period included the emerging public debate on the moral responsibilities of Pius XII and of the Holy See during the Holocaust. Also, there were fears that a Vatican document on the Jews could be interpreted as a political statement in favor of the State of Israel. Paul VI’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land in January 1964 highlighted the delicate nature of the Catholic Church and the Holy See’s diplomatic relations with Israel (they would be established only in 1993). Finally, it became clear, by the autumn of 1963, that the Council could not treat the Jews without treating other non-Christian religions, as well.

Between the spring and the summer of 1964, the text on the Jews was scheduled to become part of a separate declaration on non-Christians and then re-attached to the schema on ecumenism. Among the most important changes in the text drafted by the Secretariat in the spring of 1964 was the decision, because of opposition from Paul VI, to eliminate from the text the condemnation of “deicide”—a term that Catholics had long applied to the Jewish people that does not appear in the final text of Nostra Aetate.

After several sessions of debate on various topics, over a period of years, on October 28, 1965, the proposition that the Jews were not to be regarded as repudiated or cursed by God was accepted by a great majority at the Council: 1,821 affirmative votes, 245 negative, and 14 invalid votes. The final solemn vote on the entirety of Nostra Aetate had 2,221 affirmative votes and 88 no votes. The document achieved a large consensus; but the no votes were among the highest for all the sixteen documents approved by Vatican II.

Over the Last Sixty Years

Nostra Aetate was the beginning of a new path, and not the last word of the Catholic Church on the Jews. Some commentators noted that some expressions of Nostra Aetate revealed a supersessionist theology. In Nostra Aetate there was no request of forgiveness from those who had been persecuted by Christians. Moreover, Nostra Aetate could not deal with the issue of the theological meaning of the State of Israel and of the Land for contemporary Judaism.

But the declaration made an enormous step forward toward a new understanding of Jews by the Catholic Church, and in making clear the incompatibility of anti-Judaism and antisemitism with Catholic doctrine. Nostra Aetate was an indirect but unmistakable acknowledgment of the Shoah and of the responsibilities of anti-Jewish theology and of the Catholic Church in the history of antisemitism. It contains no expressions of hope for conversion of Jews to Catholicism. Still, Nostra Aetate dealt with antisemitism, but not directly with the more important theological issue of anti-Judaism, and had to leave out the issue of the “deicide.”

For the issues that Nostra Aetate could not address, certain post-conciliar developments in papal teaching were of utmost importance. On October 22, 1974, a new “Commission for the Catholic Church’s Religious Relations with the Jews” was instituted by Pope Paul VI. In the same year, the Commission published “Guidelines and Suggestions for Implementing the Conciliar Declaration “Nostra Aetate.” Another undeniable acceleration in the reception of Nostra Aetate took place thanks to Pope John Paul II. He was responsible for Notes on the Correct Way to Present the Jews and Judaism in Preaching and Catechesis in the Roman Catholic Church—in 1985. And during the preparation of the Great Jubilee of 2000, the Commission for the Catholic Church’s Religious Relations with the Jews published, We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah.

During the pontificate of Pope Francis, in 2015, the Commission published another landmark document in the post-conciliar reception of Nostra Aetate: “The Gifts and the Calling of God Are Irrevocable (Ro. 11:29): A Reflection on Theological Questions Pertaining to Catholic-Jewish Relations on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of Nostra Aetate.” Nostra Aetate was also the first document of Vatican II that Francis quoted in an official speech at the start of his pontificate.

It has been said that while for Jews, Nostra Aetate came too late, “for Catholic theology it came too soon and to this day has not been fully digested.” (John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965; Harvard University Press, 2012; 245.)

On the other hand, the post-conciliar official teaching of the Church on the Jews shows how much theological and magisterial development there has been since Nostra Aetate.

Revoking or simply forgetting this huge step forward in the understanding of the Gospel by the Christian tradition would have catastrophic consequences on the theological, intellectual, and spiritual balance of Catholicism.

The Debate on Nostra Aetate and Vatican II Today

The conciliar declaration “On the Relation of the Church to non-Christian Religions”—Nostra Aetate—is the shortest of the sixteen final documents of Vatican II. But its length is inversely proportional to its enormous importance in the development of the teaching of the Catholic Church. This fact tends to be forgotten now.

A neo-traditionalist Catholic culture has recently come to view “continuity,” in the sense of material continuity of teaching, as the only fundamental marker of catholicity in the interpretation of our theological tradition. But, in fact, from the point of view of Church historians, it is clear there are theological reforms that require some discontinuity: discontinuity not in the one-subject Church, which remains the same, but discontinuity in the material teaching of that same Church.

Nostra Aetate is one of the conciliar documents that represent a change in the sense of continuity and reform, but also carry some degree of discontinuity, particularly about the teaching on the Jews. The declaration on non-Christian religions is emblematic of the history of issues debated at Vatican II: having survived several attempts of being eliminated from the conciliar agenda, the document on the relationship of the Church with non-Christian religions has become inseparable from any assessment of the impact of the conciliar teachings on the Catholic Church and the world.

In this ecclesial and theological context, the case of Nostra Aetate is delicate. On the one hand, the theological rethinking operated by Vatican II can be described as ressourcement, the going back to the sources of the Tradition interpreted comprehensively. In this sense, going back to the sources included the fresh acknowledgement by Catholic theology of the Word of Jesus in the Gospel, and the Jewishness of Jesus. Revoking or simply forgetting this huge step forward in the understanding of the Gospel by the Christian tradition would have catastrophic consequences on the theological, intellectual, and spiritual balance of Catholicism and Christianity in general.

On the other hand, we cannot separate the ongoing ecclesial lapse in the memory of the importance of Vatican II and of Nostra Aetate from the current crisis of the relationship between Catholic theology and modern pluralistic democracies. In other words, Vatican II and its teaching on the Jews are two fundamental, even if hidden, pillars of the acceptance by the Church of modern religious pluralism within the context of a cultural, social, and political pluralism. That special relationship of otherness between Judaism and Christianity, as a God-given legacy, was rediscovered by Vatican II sixty years ago, and it is one of the most important mandates for our generation of believers and scholars of the relations between Judaism and Christianity.

Conclusion

Relations between Catholics and Jews are at a turning point, not only because of the changes in their relations suggested above, but due to internal changes within each tradition from theological, religious, and political points of view. In this moment, Jewish-Catholic relations are part of a larger global framing of inter-religious relations. Simply put, the Western and European narratives are no longer the ones shaping the conversation, and dynamics internal to each religious tradition are having an impact on other religions in unprecedented ways. But this is the topic for another day.

We will surely interpret Nostra Aetate differently in the decades ahead. But Jewish-Catholic relations will continue to play a unique role in how the Catholic Church responds to Jewish people, and in how it understands itself. The relationship between twenty-first century Catholicism and modern Judaism has, like it or not, become a test for the state of the world and indicative of the chance of healing of the one human family.

*See Karma Ben-Johanan, Jacob’s Younger Brother: Christian-Jewish Relations after Vatican II; Harvard University Press, 2022.