Archbishop John C. Wester heads the diocese of Santa Fe, where two national nuclear weapons laboratories are located, one of which built the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. He is a vocal advocate for dismantling these instruments of mass destruction

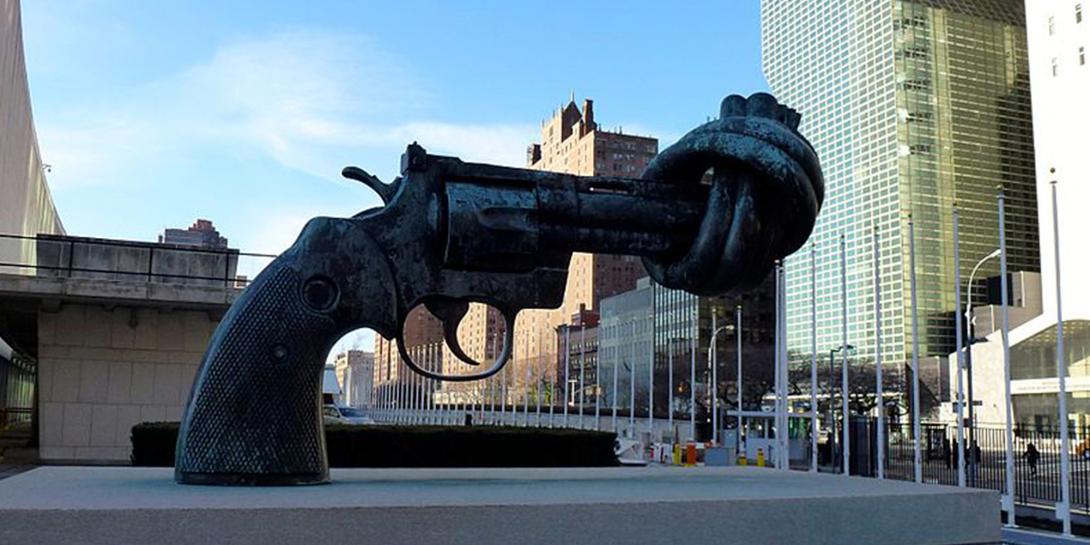

Photo credit: Wiki Commons. Non-Violence sculpture in front of UN headquarters NY.

“In September 2017, I traveled to Japan and visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a somber, sobering experience as I realized that on August 6, 1945, humanity crossed the line into the darkness of the nuclear age.”

This heartbreaking trip inspired Msgr. John C. Wester, archbishop of Santa Fe in New Mexico, to write a pastoral letter to his community to start a conversation on nuclear disarmament.

The 50 pages of “Living in the light of Christ’s peace” constitute more than a simple letter. They offer a personal, transformational experience, a summary of the social doctrine of the Church on nuclear weapons, and many comments from popes and inspiring activists like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Its conclusion proposes a plan of action and dialogue about military instruments of mass destruction.

Explaining the origin of this document, Wester emphasizes how the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe was named for the sacred faith of St. Francis, the patron saint of the environment and tireless advocate of peace and the poor. Yet “ironically, the U.S. government probably spends more on nuclear weapons within the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe than any other diocese in the country and perhaps the world.”

Why is the American government willing to invest more than $1.7 trillion in this area over the next 30 years? New Mexico hosts two of the nation’s three nuclear weapons laboratories, Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories, both located within the perimeter of the diocese. Los Alamos is the birthplace of the two atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while Sandia provides essential science and technology to resolve the nation’s most challenging security issues.

A permanent exhibit on the Manhattan Project (the code name for the nuclear project) and on the development of Los Alamos and Sandia is on display at the New Mexico History Museum in downtown Santa Fe. It exhibits all the technological progress of the American defense system.

Archbishop Wester used to take his friends to this museum, but after his visit to Japan, “it was eerie to see photos of Little Boy and Fat Man, the nicknames given to the actual Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, when I had just been in those very places only weeks before. I knew now what those bombs did to our Japanese brothers and sisters.”

After that trip, everything was different for him. “I felt disturbed by our history, the long, dark legacy of building the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, and many thousands of nuclear weapons since then,” the archbishop confides.

During World War II, the American government chose New Mexico as the perfect site for the world’s first atomic explosion, the so-called Trinity Test. Since then, the state, aptly nicknamed the Land of Enchantment, has become the country’s largest repository of nuclear weapons, with an estimated 2,500 warheads held in reserve underground at the Kirtland Air Force Base, less than two miles south of the Albuquerque International Airport.

Much of the land for building Los Alamos was seized from Native American ancestral lands and Hispanic homesteaders without adequate compensation, “continuing a legacy of colonialism and racism,” according to the archbishop.

If New Mexico were a separate country, it would be the third largest nuclear power in the world.

“We are the people who designed and built these weapons of mass destruction. We were the first to use them. We must be the people to dismantle them and make sure they are never used again,” states the archbishop, encouraging an open dialogue about the disarmament in the U.S. and internationally.

The U.S. bishops have expressed their positions in two statements, in 1993 and in 2020, defining it as a “moral task to proceed with deep cuts and ultimately to abolish these weapons entirely.” But for Wester, 2022 marked a new stage: one of dialogue and truth.

In his letter, he mentions job reports, financial data, health analysis and environmental protection investigations to present a comprehensive scenario for developing realistic strategies and concrete action plans.

According to federal budget documents, for example, Department of Energy facilities in New Mexico are slated to receive $8 billion in Fiscal Year 2022, higher than the entire state’s operating budget of $7.34 billion. Three quarters of the funds ($6 billion) are earmarked for core nuclear weapons research and production programs.

But the distribution of money is not the only concern in the diocese.

The production of plutonium “pit” bomb cores has been the choking point of industrial-scale nuclear weapons production in the U.S., ever since a 1989 FBI raid investigating environmental crimes linked to the same production in a plant near Denver. Since 1996, the Department of Energy has aggressively expanded production at the Los Alamos Lab to at least 30 pits per year, with a surge capacity of up to 80 pits per year.

At the same time, Los Alamos plans to “cap and cover” about 900,000 cubic yards of radioactive and toxic wastes, leaving them buried in unlined pits and trenches three miles uphill from the Rio Grande. That waste will remain a permanent threat to regionally shared groundwater.

Moreover, many nuclear weapons workers have become seriously ill or died from radiation and chemical exposure. Nationwide, over 130,000 workers or their families have filed claims. Within the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 17,595 claims have been filed for Los Alamos and 6,239 for Sandia; most of the claimants are Native Americans.

Wester questions whether the nuclear weapons industry really benefits New Mexicans as a whole—the evidence indicates it does not.

“During the 79 years that the nuclear weapons industry has been in New Mexico, Census Bureau data shows that our state has slipped in per capita income from 37th in 1959 to 49th in 2019.”

In contrast, the same Bureau data ranks Los Alamos County as the fourth wealthiest county in the U.S. in terms of median household income, with 79% non-Hispanic white millionaires. The archbishop points out that New Mexico is 48% Hispanic and 12% Native American, and it has the highest percentage of children and seniors living in poverty, with the exception of “white Los Alamos.”

The Catholic Church has a long history of speaking out against endemic economic inequality and institutional racism, as well as nuclear weapons. The archbishop of Santa Fe feels the urgency to address the problem and open a public debate regarding the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Vatican has been the first nation state to sign and ratify it, while the U.S. has not yet.

“It is the duty of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, the birthplace of nuclear weapons, to support that treaty while working toward universal, verifiable nuclear disarmament,” writes Wester, inviting everyone to practice Gospel-based nonviolence and walk together “toward a new future of peace, a new promised land of peace, a new culture of peace.”