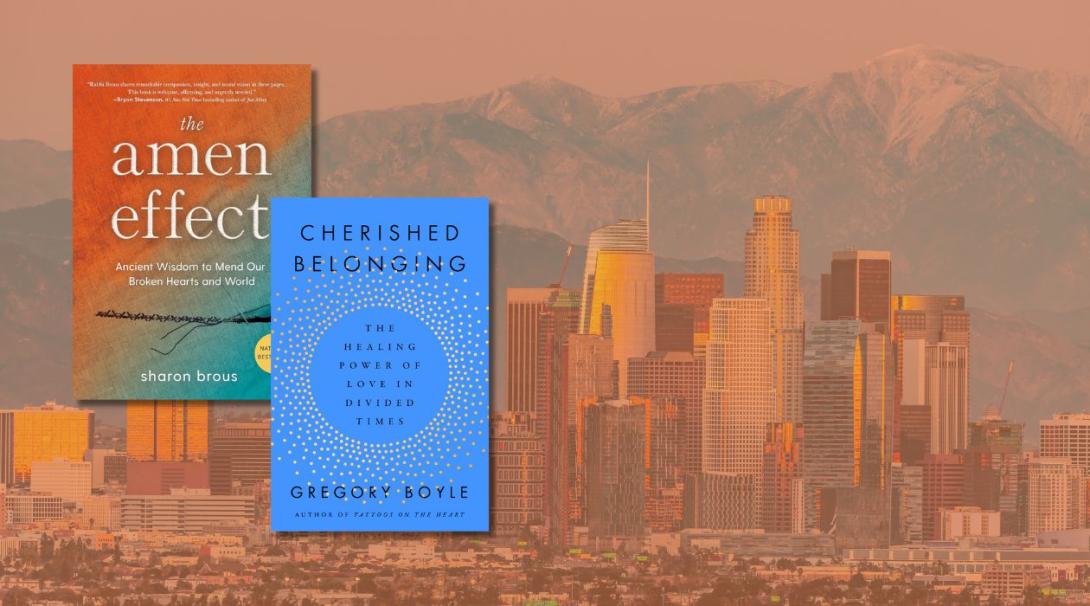

Greg Boyle and Sharon Brous are Los Angeles religious leaders, friends and collaborators on the frontlines of ministry in these wounded times. They have each written important books that diagnose in similar ways our social illness while providing remedies that reflect their particular vocations and religious traditions.

Sharon is an innovative Jewish leader, the founding and senior rabbi of IKAR, a nondenominational Jewish congregation and community in Los Angeles. Greg is a Jesuit Catholic priest who founded Homeboy Industries, which provides hope, training, and support to former gang members in Los Angeles. Though rooted in LA, each has developed a national voice as powerful story tellers and bearers of compassionate wisdom. Boyle is twenty years the elder and has written numerous books, whereas Amen Effect is Brous’ first.

I approached both authors as someone living in Los Angeles during a year of profound heartache in our community.

2025 began with two devastating fires to two of our unique communities. The Palisades fire struck first, followed a day later by the Altadena fire. I live in a town five miles south of Altadena and knew many people affected by that blaze. The whole Los Angeles area was thrown into disarray as smaller fires struck and winds blew smoke across LA County, affecting air quality and creating a kind of looming despair for days. The more than 50,000 acres that were burned is larger than the entire city of Washington, DC, and was approximately seven times larger than the Great Chicago Fire.

As we began to recover from these fires, the social equivalent of a roaring fire hit Los Angeles in the form of intentionally provocative Federal raids on immigrant communities, culminating in the deployment of National Guards and Marines intended to, as the President put it, “liberate Los Angeles” from a “foreign invasion of our country.”

As I write these words, friends are afraid to go to bus stops because they might be “taken”—a word that has entered our vocabulary to describe the sudden disappearance of immigrants from our communities. One of my friends describes talking to her daughter about what she would need to do if mom and dad were taken and didn’t return home.

These twin disasters—one natural and one cultural—have traumatized our communities and left us hungry for spiritual insight. And then, personally, I have continued to struggle through a difficult stress disorder that was diagnosed in early 2024. This ailment has been exacerbated by the stresses of 2025 and I relished the opportunity to read and reflect on these books. Both Fr. Greg and Rabbi Sharon have been at the forefront of healing efforts this year in Los Angeles, and for years they have ministered to people facing various types of trauma and struggle. Each book is overflowing with wisdom and insight, but I will highlight four things I found most nourishing.

Both books are marked by vivid, real life storytelling that reflects the authors’ vocations at the frontlines of pastoral ministry: Rabbi Brous with her congregants, and Fr. Greg with his gang members. All of their teachings are grounded in powerful stories that imbue their wisdom with spirit and empathy. They invite you into their day-to-day interactions with people going through challenges and life passages. Characters jump off the pages and into our hearts.

Each writer is also a powerful speaker and their books have a kind of authority and soul that reflects both the intensity of their ministry and their capacity as communicators. Each of them do ministry in ways that builds communities, not just individuals, and this is true of their books, too. You feel yourself being taught and guided by a fellowship of friends, as well as by each of spiritual leader as a writer.

They both identify loneliness and social isolation as a key wound in our society, and In some ways, Brous and Boyle are an unusual pairing—separated by age, gender, religious affiliation, and temperament. But their books complement each other deeply.

In some ways, Brous and Boyle are an unusual pairing—separated by age, gender, religious affiliation, and temperament. But their books complement each other deeply.

Trauma Informed

Boyle and Brous approach life as people acquainted with grief and in touch with people’s experience of trauma. This keeps their teachings from being triumphalistic or simplistic, and also creates a certain gentleness to the writing. These are people who know the fragility of life and the shadows that pass through our days.

Brous’ chapter “Hold the Healers” is but one example of how trauma-informed the authors are. In that chapter she tells of a woman who helped her understand how being a rabbi for people in sorrow means “that grief burrows deep in the body. If we fail to digest and release what we’ve absorbed, at some point we fill up with other people’s sorrow.” In his chapter, “Cruelty Points,” Boyle says: “You don’t ‘move on’ from trauma but learn to move with it. Being cherished helps you integrate your traumatic memories so they can become less dissociating. We are invited to help each other do this.”

Gentle God Talk

The gentle spirit in their writing carries into how they each speak about God. Both writers speak of God in a relational way that invites us to encounter God in each other and through each other. Building community is therefore a sacred act, a way to fully live the shalom and wholeness God intends.

In a moving reflection on Rabbinic teachings on Creation, Brous says, “From a spiritual standpoint, we are meant to live dialogically. The gift that God gave humanity from the start was the gift of one another. We have a fundamental human need to be seen as we truly are, which makes social connection not a luxury, but a necessity. Relationships are simply core to our being. It’s not good for a person to be, fundamentally, alone.” (italics in original)

Similarly, community for Boyle is, as his title says, “Cherished belonging,” which is a reflection of what God gives to us: “God’s loving expansiveness wants us to look at each other. To be the very generosity of God and to nurture each other into becoming a community of cherished belonging. We receive the sustenance, then choose to sustain each other.” In Boyle’s experience, we too often imagine a “‘Department of Corrections’ God. We want to propose a ‘Department of Connections’ God…. All of authentic spirituality is a homecoming. Home is the place where abandonment can’t ever happen.”

Their books complement each other deeply. Each is sensing in our moment a mystical opportunity, and necessity, to build communities of belonging

Wisdom Traditions

Each writer draws on wisdom traditions to enrich and deepen their insights, and for me it was refreshing to encounter new sources. Brous expertly weaves the great Rabbinic scholars of Jewish tradition. From her years of preaching, she’s learned to bring these voices from the past into the present naturally and accessibly. She wears her scholarship lightly and conversationally, and the ancient sources become voices you look forward to hearing from whenever they appear. The insights into the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, for example, were stunning, as was her layered account of the presence of angels. By my reading, the book more than lives up to the subtitle’s promise to use “Ancient Wisdom to Mend Our Broken Hearts and World.”

Boyle’s primary wisdom tradition is the hard-earned insights of the “homies” he’s lived and worked with for decades. Boyle shows how the street wisdom he encounters resonates with mystical traditions that he as a Jesuit has been immersed in. In a particularly absorbing meditation, he blends the wisdom of Louie the “homie house photographer” and Meister Eckhart, the medieval Catholic mystic, to imagine God as the “Wild One” who is “ceaselessly surprising, whose care and delight in us is hugely outsized.”

In some ways, Brous and Boyle are an unusual pairing—separated by age, gender, religious affiliation, and temperament. They each see the world through their particular lens and bring a particular style and emphasis that reflects their tradition and upbringing. But their books complement each other deeply. Each is sensing in our moment a mystical opportunity, and necessity, to build communities of belonging. I came away encouraged in the Ancient and Holy Journey to build what Martin Luther King, Jr. called “The Beloved Community.”

I conclude with these words Brous wrote, but Boyle could just as easily have penned, describing the faith community she hopes to build:

A community that sees every ritual, every service, and every gathering as an opportunity for a deepening of connectivity. It invests in people as complicated, multifaceted, wounded, beautiful individuals, each one essential to the greater whole. This kind of community…establishes spiritual anchors—regular opportunities to pray, sing, grieve, learn and reflect together. It recognizes the collective power of people of good will working to help heal the broader society and prioritizes creating pathways for the holy work to be done. It invests in the creation of sacred space that fosters not inclusion, but belonging, intimacy and authenticity, love and accountability.