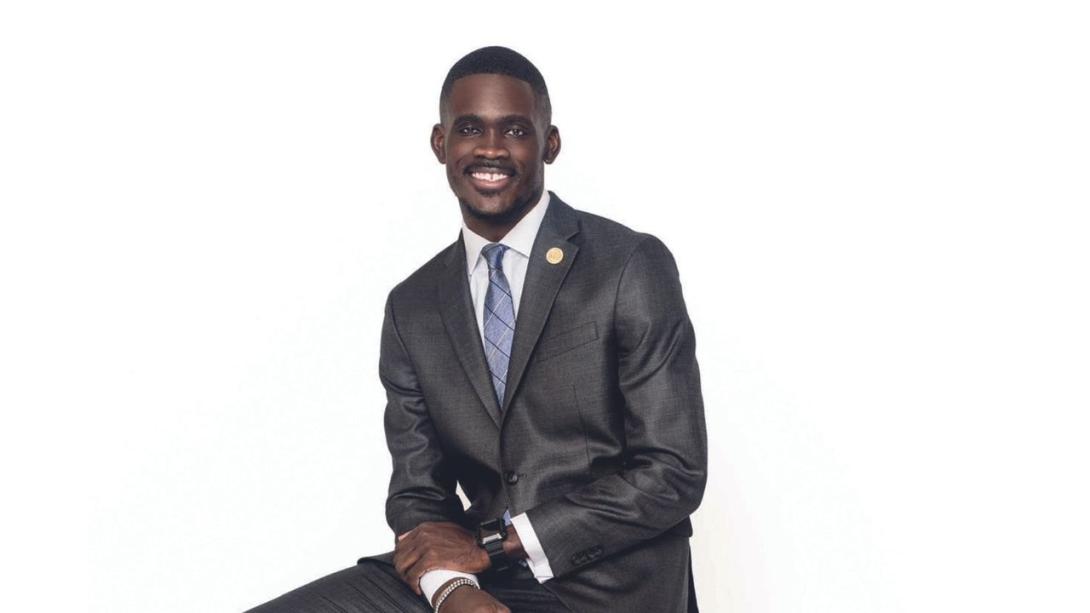

In the context of Black History Month, Living City sat down for an in-depth interview with James Woodall. Along with Dr. Mark Ellingsen, he co-authored Wired for Racism? in which they explore the question from a unique perspective. James, 29, who currently serves as public policy associate at Southern Center for Human Rights, is founder and CEO of The Major Wish Group LLC, and associate minister at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church in Marietta, Georgia. He has served as Georgia NAACP State President and as an intelligence analyst in the U.S. Army.

Photo courtesy of James Woodall

You have a very rich story, especially of involvement in human rights issues. Is it fair to say that your commitment was nurtured by your family as you were growing up?

I would say my involvement and commitment toward really improving the human condition wasn’t something that I willingly entered into. I became committed out of necessity and urgency, but, more so, I have a hope that there could be a better way.

And I genuinely believe that there is a better way. That better way is ultimately us working together and collaborating to build the beloved community.

You served in the military as an intelligence analyst. What attracted you to that career?

Once I finished my high school education, it was college, or the military, or get a job. I was at that time in the Junior ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) program.

And so I took the ASVAB (Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery) and scored really, really well, so much so that they offered me three really good job opportunities: one being a drone pilot in the US Army; another being a Defense Language Institute translator, and they finally offered me a job to become an intelligence analyst.

At the age of 17, I knew that at some point I wanted to get into politics. So I thought that being an intel analyst was both expedient and efficient.

And so I was able to balance both of those experiences: both being in college and continuing my service as a US Army intelligence analyst. So that’s the path that I went.

How did you understand that you should become a pastor? Was there an event, a moment where you had this clarity that that was what God wanted from you?

There wasn’t one particular event, and it wasn’t something that I sought out to do, even though I come from a lineage of preachers.

About January, February 2015 is when I received a call to enter ministry, and the spirit led me to a space to really undergo a journey. And that journey, ultimately, climaxed at my induction ceremony into the ministry.

How much does your faith affect your work for human rights?

My faith is very integral in the work toward human rights. It raises a question of “what is justice?” What does justice mean? For me, faith doesn’t answer questions, faith raises them.

As I’ve thought about the questions of what justice is, it brought to mind a question that shows up in the book of Genesis, “Who told you that you were naked?” (Gen. 3:11) What significance does such a question have on our human condition, particularly around questions of how we find ourselves positioned before God?

Because if we are God’s creation, why do we treat each other so poorly? Why do we ignore those who are homeless? Why do we throw in and incarcerate more people in this state of Georgia and in this country of the US than any other country in the world?

In the words of the late African-American author James Baldwin, it is long past time for us to lift the veil to see who we really are.

And so that regards your question of faith, informing my function as a preacher, as clergy, as faith leader, as civil rights leader.

It is crucial for us to have a faith that really grounds us in darkness. For the darkness though it is dark, in some ways, is beautiful, because that is exactly the space in which God creates (Gen 1:1). It is that darkness that allows for us to truly appreciate and embrace the very presence of our Almighty God.

Can you share about your work at the NAACP and the Southern Center for Human Rights. What are your major projects, what is close to your heart in this work?

At my time at the NAACP, one of my main priorities was the environment, addressing issues related to coal ash being deposited into groundwater.

That water is contaminated for people, which they use for everyday life. So we challenged that practice, and we were successful in getting legislation passed to address those deposits, and these ash ponds had to be aligned in order to not contaminate the ground supply of water.

Secondly, we were interested in voting rights. In 2019, Georgia was making an appropriation of about $550 million to implement a new electoral system. And we were saying that this system, which relies on QR codes, makes it impossible for us to verify that what is on the QR code is exactly what voters wanted.

As we saw Georgia Senate Bill 202 taking shape, we were trying to get our secretary of state to understand the difficulty and the danger in this legislation. Now that the bill has become law, we continue to work in federal court and do all the work there.

Then finally, we obviously think about the criminal justice system and the criminal legal system. I make that distinction because the criminal legal system is one in which legal processes often work together to cage or kill human beings. It is not a criminal justice system.

The criminal justice system is a network of supporters and institutional actors that works to free us from that human conditioning. That’s why I joined the staff of the Southern Center for Human Rights. As an example, we have succeeded in getting the State of Georgia to repeal the right of private citizens to arrest other private citizens.

So those have been the three areas of emphasis in my career and in my journey, but more importantly in my profession.

February is Black History Month in North America. How do you see the state of race relations now in the United States?

To be honest, I believe that the very presence of the concept of race itself is dehumanizing. I believe it has contributed to the deterioration of the social fabric in which we should be able to really collaborate and work together toward the common end of justice.

The very presence of race allows for there to be an “other.”

So that’s what I think. The mere presence of race itself is dehumanizing, is dangerous. And so there can never be positive race relations as long as there’s White, Black and other.

What can we as people of faith do to overcome this thinking?

What we must do is first listen to the Scripture and raise the questions of who told us we were naked, and really sit with the tension of not knowing the answer.

We, as believers of Christianity, often rush toward resolution. We rush toward resolution with Jesus on the cross. We rush toward resolution when really all the disciples are on the cross. We try to find the resolution and all things good, rather than sitting with the tension of why or who told us that we were naked.

If we are to really answer the question of what we must do, we must first understand why we are here in the first place.

We have to be willing to be vulnerable enough to actually become neighbors. Because when we’re no longer naked, we are no longer in a place in which we operate by ourselves, as opposed to being part of a larger community in which we treat each other with love and dignity and respect.

There’s also the tendency by some activists to emphasize the differences, to be recognized as Blacks or as Latinos, which sometimes makes it so difficult to build relationships. I think there are moments to showcase the difference identities, but what can we do so that this does not impede the rebuilding of the social fabric?

When we talk about the nakedness of humankind, it becomes difficult to remove heritage and culture in which we have so many variants. And it’s important for us to recognize that distinction in relation to the removal of race, not of diversity.

What I can suggest, as we engage in building these communities, is that every single community, every single culture, every single ethnicity has space for authentic being.

This is a beautiful thing: that we all are able to learn from each other, and that no one is more important or more efficient or effective than the other.

We should be saying, “You are human, too, and I’m looking out for you just as well as I’m looking out for me, because we’re all part of one big community.”

It is a good thing to realize how much we are influenced by unconscious bias. How can we overcome this unconscious bias that each one of us has?

I would encourage people to get the book Wired for Racism? because we talk about that, and I don’t want to spoil the book. But generally speaking, I think it’s important that we continue to do what I said: really embrace the diversity of our neighbors, and really engage in relationship building because those have very positive impacts on our brain.

In the book we talk about education and how our educational system is organized. We talk about housing and farming and agriculture. We talk about the mass incarceration complex here in this country.

We talk about reparations. How do we address historical wrongs that have been issues over the course of our human history? What about technology and mass media?

So I encourage people to read it and see how we approach that question with very specific recommendations for not just interpersonal relationships, but also societal changes that need to be made.

What is your dream for America and for humanity in general?

My dream for America is ultimately to repent for her sins, so that we can be able to live in a world that allows for everyone to be free. That’s my dream for repentance, reconciliation and ultimate redemption.

That’s my dream. Because in the words of civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, “no one’s free until everybody’s free.”

We must rise and declare what is right, what is just, and ultimately, what is true. And what is true is that we were all made in the image of God. And that presents to us a unique challenge. But it also presents to us a unique opportunity for us to be able to live in a way that God will be pleased.

And so, we are a people of hope, but our hope is that we can one day hear the Lord say, “Well done, my good and faithful servant.” That is my dream for this country and ultimately for this world: for us to live in repentance; for us to experience and live in the redeeming grace and power of love, and most of all, at the end of all of this, to hear those words, “Well done my good and faithful servant.”

James Woodall lives in Atlanta. He has been named to Georgia Southern’s “40 under 40,” and “Alumnus of the Year” in 2020 and was named a 2021 #Atlanta500 Leader by Atlanta Magazine.