Photo by commons.wikimedia.org

Gabriel Marcel (1889–1973) was a French philosopher, playwright and composer who belonged to a school of philosophy in which the human person is the focus of reflection.

Quoting Marcel’s Creative Fidelity, Pope Francis in “Fratelli Tutti” observes how human beings can never fully know themselves “apart from an encounter with other persons: ‘I communicate effectively with myself only insofar as I communicate with others.’” (63)

Marcel taught philosophy at various schools and universities throughout France, but this was interrupted by World War I. During that conflict he directed a Red Cross unit that sought to find soldiers missing in action.

This experience marked a turning point in his life. His diaries from around this time show how he refused to treat the lost as just numbers or cases. He saw them as helpless fellow beings, and their need moved him deeply.

As human beings, he remarked, we are homo viator, that is, people on a journey or wanderers. In a lecture given in Frankfurt, Germany in 1964, he explained the role of the philosopher as being a “watchman,” that is, a sentinel who keeps watch over who we are.

In “Homo Viator,” he compared his work to that of a mother who awakens her children to feed them. He described how “to awaken, to feed, to teach how to breathe: these essential life-functions have their exact correspondence at the level of philosophy.” Philosophy prepares us, he says, “for the ineffable surprise of the eternal tomorrow.”

A character in one of his plays asks, “What are you living on?” Marcel comments that if he were to ask himself this same question, he would explain how what sustained him has been, in addition to his family, what he calls “an invisible support.” Life, he holds, is a preparation for that eternal tomorrow, whose “magnetic” pull alone can make persons of us.

“The View of Delft”

Because he was also a dramatist, poet and composer, Marcel very often does not begin his philosophical deliberations “with abstract definitions and dialectical argumentation,” which would merely discourage his readers or audience, as he indicates in his “Perspectives on the Broken World.”

Our world, he believes, is dominated by the notion of function, and we can end up considering human beings in terms of their functions. Nonetheless, living is not just about mere activity.

Marcel asserts that life in a world “centered on function leads to despair, because such a world is empty, it rings hollow.”

There is a need for “recollection,” which is defined as “a relaxation, a letting go” involving “abandoning to… [and] relaxing in the presence” of who we are. He observes how the process of recollection “does not [simply] consist in looking at something, [rather] it is a retrieval, a renewal.”

This entry into oneself does not imply a purely turning back on ourselves. Marcel observes how here we are “in the presence of the paradox of mystery, whereby the self into which I return ceases.”

So it actually involves an emptying of self, and thus St. Paul’s statement that “you are not your own” (1 Cor 6:19) becomes true both ontologically and concretely.

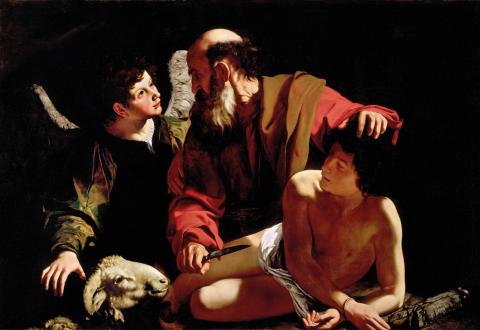

According to Marcel, it is in drama, music and art that “metaphysical thought becomes conscious and defines itself concretely.” In “The Mystery of Being,” while discussing the human person, Marcel gives the example of “The View of Delft,” a painting by Johannes Vermeer, a 17th century Dutch master.

Marcel explains how we as human beings living “in-a-situation” can develop creatively. When it comes to understanding who we are, there can be no “global abstraction, [nor] any final high terrace to which we can climb by means of abstract thought.”

In the action of a painter like Vermeer we can, for example, see disclosed the power of our “inwardness” as persons in the transformation of our “being-in-a-situation.” Marcel outlines how in viewing the painting we realize that “if for Vermeer the view of Delft had been a mere spectacle, if he himself could have been reduced to a mere spectator, he would never have been able to paint his picture.”

It is in an artwork such as Vermeer’s that we can discover the uniqueness of each person’s ‘inwardness.’ Vermeer did not paint “The View of Delft” as he would another place. Indeed, if he had lived “somewhere else, though he still might have been an artist, he would not have been Vermeer.”

Marcel describes how it is only when we cease to be mere spectators that we discover how we as human beings can admire and contemplate a painting. In this way we participate in the work of the artist realizing that admiration is equally “to create… to be receptive in an active, alert manner.”

The artist’s work can, of course, be analyzed at the level of its being an object or a thing and as coming from a particular school of art, exemplifying different artistic methods. But we can also somehow encounter the experience of the artist as a person in the work.

Marcel uses the word ‘encounter’ in his philosophy very deliberately because he believes that “there cannot be an encounter or a meeting in the fullest sense except between beings endowed with a certain inwardness.” It is in the work of art that we can stand at the threshold of such experiences.

So, using the artistic example of Vermeer, Marcel articulates how constitutive of our human nature is the reality that “there is creative development as soon as there is being in a situation.”

To love someone is to say you will never die

In terms of his philosophical approach, Marcel is often called an existentialist. But he would not agree. Indeed, his reflections on human mortality surely shatter any such simplistic categorization. Gabriel Marcel’s mother died when he was young, and then the death of his wife and other family members through illness deeply affected him.

Death in a way truly tests how we experience and understand “presence.” Reading about the death of someone in a newspaper is often nothing more than an object of notification or curiosity. But in his “Perspectives,” Marcel points out that, when it comes to a person we love and “who has been given to me as a presence,” in the experience of their death we are speaking of how to hold on to that presence.

Marcel explains how a “presence” is “a reality.” This means that I cannot treat “the other as simply placed there, positioned in front of me.” There arises “between the other and me a relationship which in a certain sense goes way beyond the conscious awareness I may have of it.”

Marcel holds that the “other person is not only before me, the other is also within me.” The purely physical categories are totally transcended. He outlines how in the death of a loved one “even when I can neither touch you nor see you, I feel it, you are with me.” It would be a complete betrayal of who you are as a person “not to be assured of this.”

So, Marcel describes how it is in experiencing “the death of those we love” that we can recapture the truth of reality. It is in these situations that we face ultimate realities.

There is, in fact, no such thing as death in general. It is encountered close to us and not as an abstraction.

In “Homo Viator,” he asserts that the death of a friend or a relative is “within reach of our spiritual sight” if we, for example, keep vigil at the bedside of a loved one who is dying. What are we communicating in our care and solicitude? Marcel remarks on how “to love a being… is to say you, you in particular, will never die.”

He says that if we assent to the death of a person, we surrender them to death. Instead, to say that I love you means that that love will never die.

It is experienced in a new way, that is, in the presence of God who is love. Our experiences are transitory and fleeting, but in God’s presence we behold and experience an eternity of God’s unconditional love. To say that the “tenderly loved being no longer exists” is a betrayal of such love.

As human persons we are embodied beings, but we are not thereby entombed. As Jesus says, God is of the living and not of the dead, since “for him all are alive.” In light of this we are challenged to live fully alive and not go around as if we are half dead.

There is an Irish proverb that is appropriate here. It says of those who have died that “the candle is quenched only because a new day has dawned.”

It is fitting that in “Homo Viator” Marcel claims that he wishes to speak as “a philosopher of the threshold.” In a poem he wrote:

“When we try to push back the veil of clouds / which separates us from the other realm / guide our novice gesture! / And when the appointed hour chimes, awaken in us / The light-hearted spirit of the traveler, who fastens on his sack, / while outside the misted windows there appears / the gentle dawning of daybreak!”