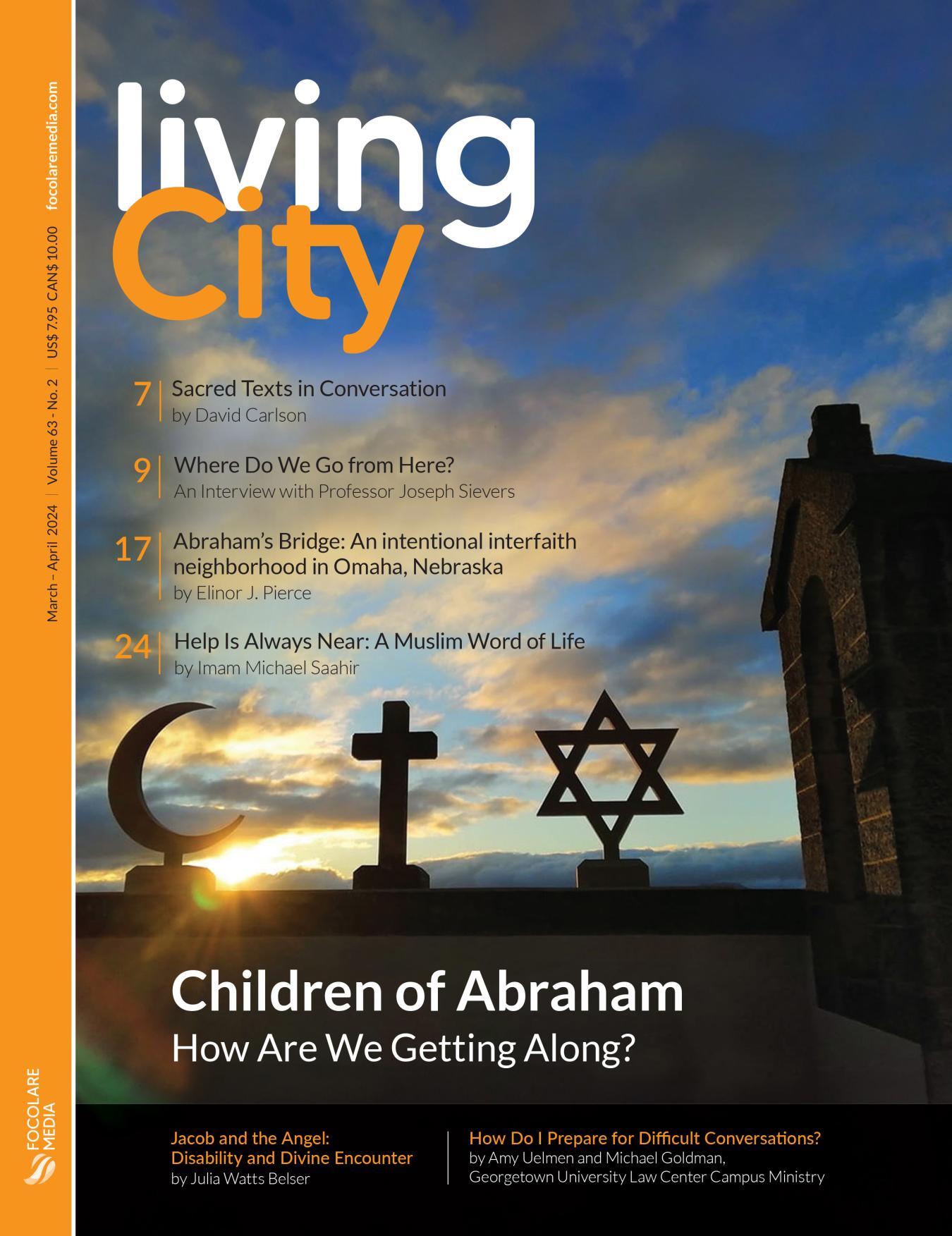

An exploration of interfaith dialogue, prompted by unexpected encounters with sacred texts from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

© Photo by Molostock | Adobe Stoc

Because I was raised in a conservative religious tradition, I knew no one involved in interfaith dialogue. The message I was given was that the rest of the world needed to change and join the branch of Christianity that I was in. Fifty-five years later, while finishing Countering Religious Extremism: The Healing Power of Spiritual Friendships for New City Press, I maybe shouldn’t have been surprised to hear a voice within me asking, “Are you sure that interfaith is the journey you should be taking?”

The answer to my inner question came in an unexpected way, yet was attuned to my heart, my mind, and my need. In the spring of 2013, I was teaching another semester of religious studies at Franklin College in Indiana. That week in April was also Holy Week in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which meant I was struggling to balance my teaching responsibilities—creating class plans and grading tests and papers—with my desire, in the evenings, to attend the many Holy Week services that precede Easter.

I assigned students in my freshman-level introduction to religion class a paper that highlighted a significant aspect of one of the religions we’d studied that semester. I thought I had graded all of these papers, but on that morning in April, I found a paper hidden beneath a stack of books on my desk. I should have graded the paper days before, but God had other designs.

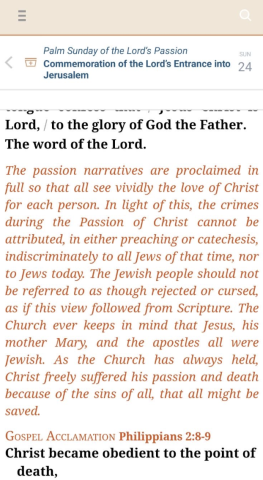

In the student’s paper on Judaism, I read this quotation from Rabbi Harold Greenstein. “The Talmud teaches that ‘in the place where a repentant sinner stands, even the righteous who have never sinned cannot stand.’” I wrote a note in the margin, commenting that this was an important and significant contribution to our understanding of Judaism. As I moved on to other work, however, the rabbinic comment faded from my conscious mind.

In the Holy Week service that night, the scripture passage told the story of a woman who, in gratitude for God’s forgiveness, anointed Jesus’ head and feet with costly perfume and her tears. The disciples were scandalized and protested that the woman’s action was a waste of money that could have been better spent on helping the poor. Jesus, however, responded by saying that what the woman did was a “beautiful thing,” before adding, “Truly, I say to you, wherever this gospel is preached in the whole world, what she had done will be told in memory of her.”

As I heard the story of the forgiven woman being chanted, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand up as the Talmudic passage came flooding back into my mind: “In the place where a repentant sinner stands, even the righteous who have never sinned cannot stand.” In that moment, in my heart as much as my mind, text met text, and I was cast headlong into a deeper understanding of the woman’s joy. The Rabbinic saying opened me to understand that the woman had indeed stood “in the place where a repentant sinner stands,” a place where not even a righteous person who has never sinned could stand.

The two texts, I realized, were having a conversation. Together, the Talmudic passage and the New Testament story shed light on the deep joy that comes when we know God has forgiven us, even as the story exposes the self-righteousness that prevents us from knowing the mercy of God. The beautiful harmony of the two passages, one rabbinic and one gospel, overwhelmed me.

Later that night, the joy I had experienced in the evening service was so strong that I couldn’t fall asleep. I felt an irresistible urge to open my computer in the hope of finding a text in Islam that matched the uncanny conversation between the other two passages.

I found it impossible not to believe God was leading me when the first passage that appeared on my computer screen was a passage in the Hadith, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad: “Abu Sirma reported that when the time of the death of Abu Ayyub Ansari drew near, he said: I used to conceal from you which I heard from Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) and I heard Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) as saying: Had you not committed sin, Allah would have brought into existence a creation that would have committed sin (and Allah) would have forgiven them.”

As I read this passage, the three-fold harmony of the rabbinic saying, the gospel story, and the saying from the Hadiths washed over me. Each offered a lesson about God’s mercy. In conversation with one another, however, they shed a probing and healing light that was more than the sum of the three parts.

The Rabbinic saying offers the powerful insight that there is no experience greater for human beings than to know we have been forgiven by God. In that moment of being forgiven, in that space, the Talmud teaches that the forgiven person stands on holy ground, inside a circle that those who consider themselves righteous and sinless can never enter. What a wonderful antidote to the common human tendency, like Adam and Eve in the garden, to hide our flaws from God, others, and ourselves.

From the New Testament story, I witnessed the woman’s joy and abandonment of decorum as she was washed in the forgiveness of God. The story drew me into the woman’s heart as she stood in the holiest of places described in the Talmud, the place where she experienced, not judgment for her sins, but God’s forgiveness. As she stood in that circle of forgiveness, clean and new in the presence of God, she invited me to drop my pretensions, to relinquish my need to appear holy, and to be washed clean.

From the Islamic Hadith, I was enveloped in even greater light as I was drawn into the heart of God, the God who loves nothing more than to forgive sinners. What else can any of us do but submit to a God whose greatest joy is to forgive us, cleanse us, make us new?

I was overwhelmed with wonder at what surely, I thought, was a sign, an answer to that inner voice that whispered, “Are you sure that interfaith is the journey that you should be taking?” The threefold illumination radiating from these texts seemed a sure sign to me that God was directing me to embrace interfaith and to let interfaith embrace me.

I have spent my working life studying sacred texts. But sacred texts have been more than my career. They have been my great love. Even before what I will always remember as “the night of the three texts,” I knew from spiritual friendships with Jews, Muslims, and other Christians that the mercy of God is at the center of our faiths. Perhaps God knew that the path that would forever change my understanding of Divine Mercy would be through an encounter, an interfaith encounter, with sacred texts.

Even before what I will always remember as “the night of the three texts,” I knew from spiritual friendships with Jews, Muslims, and other Christians that the mercy of God is at the center of our faiths.

As God sometimes ordains in our lives, events can reinforce the lessons we are meant to learn. Four years after that night, “the night of the three texts,” I was diagnosed with cancer. My treatment plan included two bouts of radiation months apart. Over those months of treatment and the numerous trips to the hospital, I developed friendships with the wonderful doctors and nurses who work in the field of oncology. Many conversations about religion, faith, and interfaith occurred once the medical staff discovered that I taught religious studies and biblical studies. Becoming friends with the medical staff made my treatments more than bearable, and I believe those friendships increased the healing power of my treatments.

No one will ever forget the day when they are told, “You have cancer.” But that day was nothing compared to the day when my doctor told me that the treatments had succeeded and my tumor was dormant.

I would never say that I’m glad I contracted cancer, even as I will never say I’m glad I have sinned against God and my neighbor. But it is because cancer is so serious that the news of my remission was so unforgettable. In a similar way, it is only because sin is so serious that God’s delight in forgiving us is so astonishing, so freeing, and so life-changing. Let us live every day in the wonder of God’s mercy.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like...