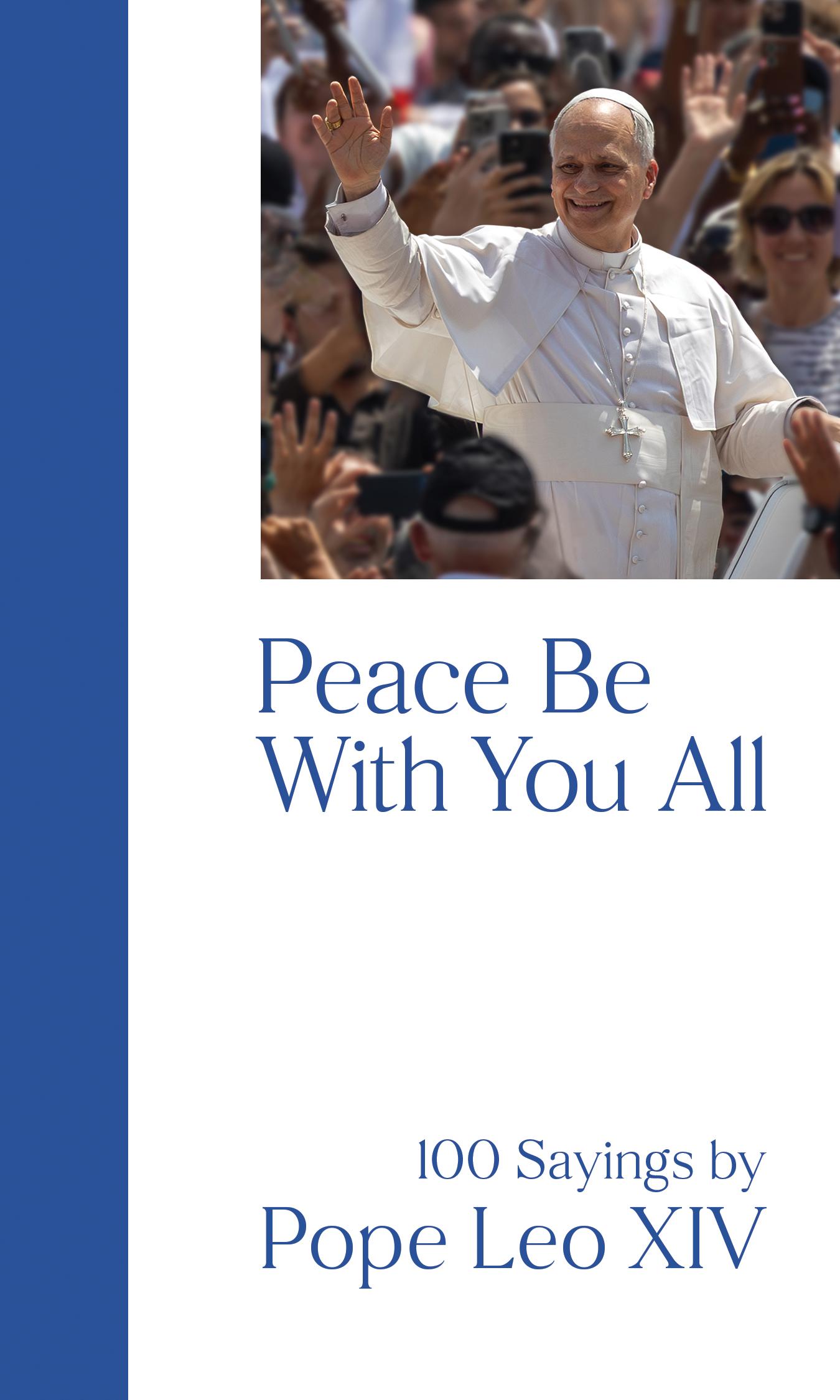

Photo by Hu Chen on Unsplash

Most of the time we choose our own battles. We conceive some plan and we activate it, like the mountain climber whose gaze is fixed on the summit, like the lion closing in on its prey. There may be a certain danger involved, even sought after, but the rush of adrenalin is part of the pleasure. Risk is involved, but it is a calculated risk.

All of this satisfies the human ego, whose chief preoccupation is striving to be in control of every situation, to ensure a favorable outcome. It is the case with an invading army, which only moves when it is sure of victory. The day and the hour are chosen when the other side is at its most vulnerable.

Yet sometimes we do not have the luxury of choosing our own battles. Sometimes our peaceful existence may be shattered by a tragic event, a serious illness, a financial crisis, a family rift. Or even, as in Ukraine, by missiles exploding on our streets.

Here there is danger, but instead of the pleasurable rush of adrenalin, there is the paralyzing fear of what might happen. There is no such thing as a calculated risk, but only the dread induced by an uncertain future.

In such a situation, life is reduced to a simple question: Do I stay and deal with this, or do I run away?

Along with this question, there is also a heightening of the consciousness of my individual role in the scheme of things. I feel myself addressed personally: What are you going to do?

Unlike the mob gathering for a riot, I cannot hide in the crowd. Even if the others turn their backs, walk away, I will still be questioned personally: Are you also going to walk away? Yes or no?

If I set out to climb a mountain, and my strength fails, there is no real test of character involved. Mostly it is a question of the ego deciding whether it is more pleasurable to return to the comfort of the couch and a cup of tea or to enjoy the self-satisfaction of completing a difficult task.

Instead, very often when a crisis lands on my doorstep, my response has consequences for other people. I may have to put myself in danger to save someone’s life, perhaps going to the rescue of a drowning person in a rough sea, confronting an attacker who is assaulting another person.

Or less dramatically, taking care of an elderly relative, or dealing with a sink full of dirty dishes.

Courage cannot be commanded; for certain difficult tasks, only a volunteer will do.

This is the case with Isaiah the prophet. The Lord asks, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” Isaiah replies, “Here I am! Send me.”

At the pass of Thermopylae, Leonidas asked for volunteers to hold off the vast invading Persian army so as to allow the rest of the Greek forces to retreat safely. A thousand remained and fought to the last man.

True courage is often hidden under a veil of real humility. Dag Hammarskjöld, The UN Secretary General from 1953 to 1961, had to face up to numerous global crises during his tenure. Refusing to remain secure in his office at the UN building, he often flew directly into a conflict zone.

In all of this, he refused to describe himself as “courageous.” For him it was simply a question of it being morally unacceptable to run away when duty called. In the spiritual diary that he kept throughout his life, he writes:

“Courage? On the level where the only thing that counts is a man’s loyalty to himself, the word has no meaning. Was he brave? No, just logical.”

Dag Hammarskjöld died in a plane crash in 1961 on this way to initiate peace talks in the newly independent Congo. In that same year, we find this writing in his diary:

“I came to a time and place where I realized that the way leads to a triumph which is a catastrophe, and to a catastrophe which is a triumph, that the price for committing one’s life would be reproach, and that the only elevation possible to a man lies in the depths of humiliation.

“After that, the word ‘courage’ lost its meaning, since nothing could be taken away from me.”

First published in New City, London