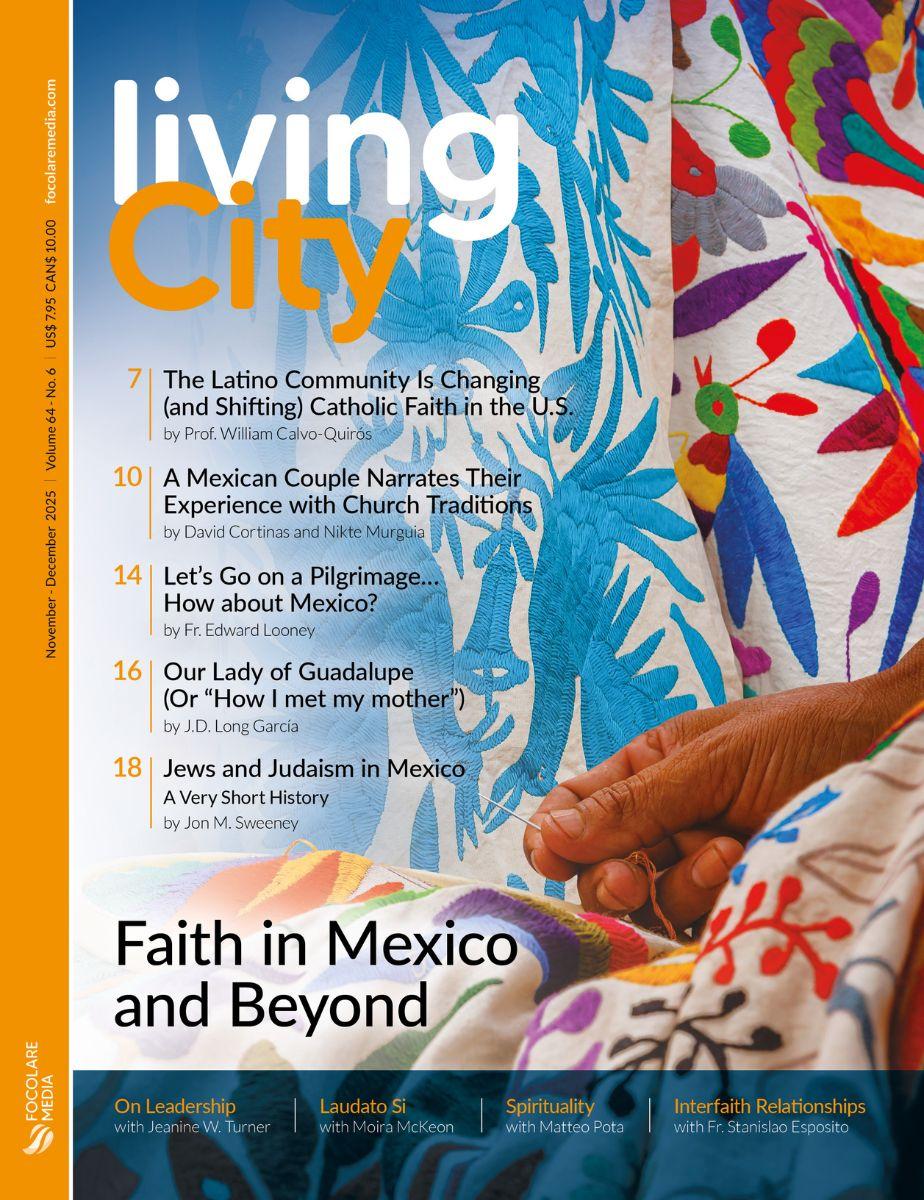

Virgin of Guadalupe at the St. Catherine of Siena Parish in Phoenix

I guess you could call me a late bloomer when it comes to Our Lady of Guadalupe. Kids on my little league baseball team sometimes wore shirts with her image on it. I’d also see her likeness in locally owned shops and restaurants.

My family moved to Arizona from the Caribbean when I was going into third grade. Our Lady of Guadalupe is not as popular back home as she is in the Southwest. Frankly, for years, I didn’t realize the depiction was of the Blessed Mother. It felt like a Mexican thing, and I’m not Mexican.

After college, I was hired as the bilingual managing editor at The Catholic Sun, the newspaper serving the Diocese of Phoenix. Given my Latin American roots, everyone assumed I knew all about Our Lady of Guadalupe. I did not, so I did some research and learned the story.

In 1531, the Blessed Mother appeared to an indigenous man named Juan Diego. She first appeared to him at dawn on a hill, called Tepeyac. An Aztec goddess, called “Tonantzin” or “Our Mother,” had been venerated at the site for some time.

Juan Diego, who was on his way to church, heard beautiful singing coming from the top of the hill. He stopped to listen. Once the singing stopped, he heard a voice call him by name. He felt no fear, according to the Nican Mopohua, a traditional account of the apparition written in Nahuatl, Juan Diego’s native tongue.

At the top of the hill, he met a woman whose clothing appeared to burst out rays of light, like the sun.

The woman revealed herself as the Mother of God. She commissioned Juan Diego to ask the local bishop to build a church on the hill and dedicate it to her. Juan Diego met with the bishop, but the bishop did not believe him.

He reported back to Our Lady of Guadalupe and asked her to send someone else—someone with more influence. She said no. This was Juan Diego’s message to deliver, and she encouraged him to ask again. On the second visit, the bishop remained skeptical and asked Juan Diego for some kind of sign to prove his story.

The next day, Juan Diego needed to care for his ailing uncle, Juan Bernardino. His uncle appeared to be dying, so Juan Diego headed out to get a priest. He had to pass by Tepeyac, but this time took a different route to avoid the Virgin Mother. She found him anyway.

Juan Diego explained the situation and assured Our Lady of Guadalupe that he would be back to talk to her after he took care of his uncle. Our Lady seemed unimpressed. According to the traditional account, she said something along the lines of:

Listen carefully, my son. What you fear, what worries you is nothing. Don’t let your heart be troubled. Don’t be afraid of that sickness or any other. Am I not here? I am your mother, and I am protecting you. Am I not the source of your life? You are in the hollow of my mantle when I cross my arms. What else do you need?

She assured him that his uncle would be healed of his illness.

I was taking photos at St. Catherine of Siena Parish in Phoenix when I felt it…. All at once, I felt her presence. I stopped taking photos and started praying.

As to the sign the bishop requested, she sent Juan Diego to the top of the hill to gather what flowers he found there. When he returned, the Blessed Mother arranged the flowers in Juan Diego’s mantle, or tilma, and asked him to present the flowers to the bishop. When Juan Diego did so, the miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was revealed on his mantle.

Seeing the flowers and the image, the bishop at last believed.

For my part, I must confess that the story alone did not make me a devotee. It was nice, I thought, but it still felt like someone else’s devotion. I didn’t really get it until, one year, I reported on the Our Lady of Guadalupe celebrations at several Phoenix parishes.

Preparations for her December 12 feast day can be prayerful, like a novena, but almost always include cooking as well. On December 11, those devoted to Our Lady of Guadalupe—Guadalupanos—stay up late and sing her a version of a traditional birthday song, “Las Mañanitas.” Festivities often include processions, mariachis, traditional Mexican dancers, veneration of the image and the celebration of mass.

I was taking photos at St. Catherine of Siena Parish in Phoenix when I felt it. I got to the celebration early, but still had to park several blocks from the church. It was dark and chilly. All I could think about, as I shuffled down the sidewalk, was how to take photos in such low-light conditions. I didn’t bring a tripod.

Traditional Mexican dancers, called matachines, had already gathered alongside the musicians. I threaded my way through the crowd and took a few photos. It was a weekday, and all these families—including children—were at church so late. I didn’t understand.

It must have been after 10 p.m. when mass ended. But the celebration continued in the parking lot: music, dancing, champurrado (like Mexican hot chocolate). A crowd formed outside the church around the statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which was behind protective glass.

As I took photos, I couldn’t help noticing the deep signs of affection. People prayed before the statue, some carrying their sleeping children in their arms. They put their hands on the glass, or kissed it, and left flowers. They wept.

All at once, I felt her presence. I stopped taking photos and started praying. This was not some ancient ritual or cultural celebration. This went well beyond that.

The devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe recalls the moment in history when God sent his own mother to intervene and intercede amid violence on behalf of his beloved children. Many Indigenous people had lost their lives at the hands of the Spanish conquistadors.

The people who gather to celebrate Our Lady of Guadalupe recognize her as their mother. They dance for her and sing her happy birthday. They share food and drink. They come to her house—the church—and stay late. And they thank her for the great miracles she has helped bring about in their lives.

I was taking photos at St. Catherine of Siena Parish in Phoenix when I felt it…. All at once, I felt her presence. I stopped taking photos and started praying.

The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe itself reminds us of the Incarnation. It depicts the Virgin Mother with a black ribbon around her waist, which made clear to her Indigenous audience that she was pregnant. Over her womb is a four-petaled flower, which symbolized divinity.

The stars in her mantle and the moon under her feet recall Revelation 12:1. Her face, which reflects a mix of Indigenous and European characteristics, prefigures the coming together of culture and race. The apparition sparked the evangelization of the Americas.

The image helps us remember that the Blessed Mother is present, and that she is our mother.

I have had the privilege of seeing the miraculous image with my own eyes, both as a pilgrim and as a journalist at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. I have walked up the same hill where she appeared to Juan Diego. And I was there, in the balcony, when Pope Francis arrived during his pastoral visit to Mexico.

But it would have meant so much less were it not for my Mexican brothers and sisters in Arizona who introduced me to Our Lady of Guadalupe. Their love and devotion to her opened my heart to feel her presence and to trust in her intercession. Their faith converted me, not unlike the way Juan Diego brought about the conversion of the skeptical bishop.

Over my years as a journalist, immigrant families have welcomed me into their homes and shared their story. Mexican families almost always have an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe right by the front door. (They might also have her image in the kitchen, the living room, the laundry room—one image is rarely enough. In our home, we have three, along with two small statues. Can you have too many images of your mother?)

The image reminds them—and now me—of what God did for the people of the Americas. The image helps us remember that the Blessed Mother is present, and that she is our mother. We need not let our hearts be troubled. We are in the hollow of her mantle when she crosses her arms. What else do we need?