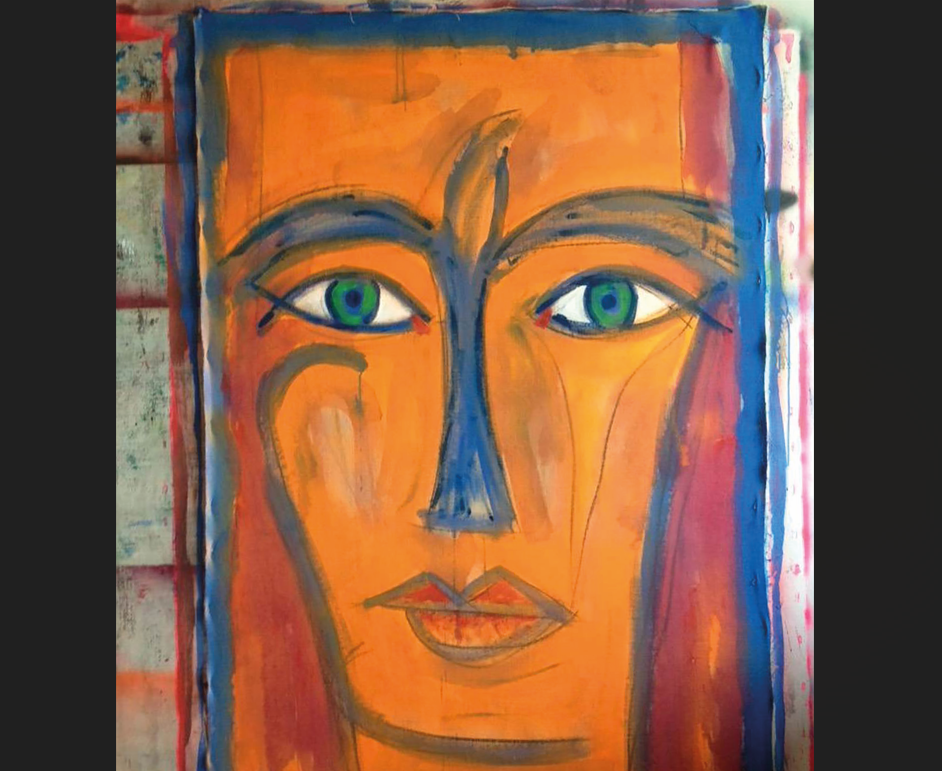

Photo by Michel Pochet

Emmanuel Levinas (1905–1995) was a French Jewish philosopher born in Kaunas, Lithuania. He studied philosophy in Strasburg, France. In 1940 he was captured by the Nazis and imprisoned in a labor camp for officers. His Lithuanian family was murdered, and his wife and daughters were hidden by religious sisters in Orléans. From 1947 onwards he took up various academic positions in France.

Speaking about Martin Buber and Emmanuel Levinas, St. John Paul II once described how their writings are quite close to the thought of St Thomas Aquinas. But in these philosophers the pathway to understanding reality and ourselves passes not through careful considerations of “being” and “existence,” but through people and their meeting each other.

It is through the “I” and the “you” of each other as human beings that we comprehend the 'other.'

New horizons on transcendence

Levinas developed a new approach to arrive at the transcendent. The search for the beyond is usually mediated through the sacred, but for Levinas it is in the face of the 'other' that we encounter and directly experience the beyond.

To Levinas, this is not an abstract reality, since that would be a false transcendence. The 'other' “demands me, requires me, summons me” (Alterity and Transcendence).Levinas explains how “the face-to-face is a relation in which the I frees itself from being limited to itself.”

In the encounter with the other person we experience an “exodus from that limitation of the I to itself.”

Of course, many other philosophers like Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Buber and Gabriel Marcel reflected on what is often called a philosophy of the “other.” The challenge is, according to Levinas, not to get caught up in a tangle of abstractions. It is in loving one’s neighbor and “working on oneself” that we can “go toward the Other where he is truly other.” Indeed, he calls this emphasis on “the presence” and “proximity of persons” a “new spirituality.” (88)

Levinas observes how when we address another person it causes an “ethical disturbance” within us. We cannot remain indifferent to them. It is as if “the tranquility of the perseverance of my being, in my egoism” is shattered in the encounter.

So, when I meet a stranger, I am provoked to go outside of myself, and it is then that “all thought is subordinated to the ethical relation, to the infinitely other in the other person.” (97)

Levinas holds that love is not just consciousness of the 'other.' Any thinking (cogito) about the 'other' follows on from our preexisting “vigilance for the other.”

Whereas Descartes’ emphasis was on the cogito in the famous dictum “I think, therefore, I am,” Levinas’ emphasis is on the priority of the 'other.' Putting it in philosophical terms, he says “the transcendental I in its nakedness comes from the awakening by and for the other.”

The proximity of the 'other'

Levinas highlights what he calls “the proximity of the other,” seeing it as putting into question our very being as human persons. He speaks of how we can, of course, live purely at the level of “there is” (il y a). The concept of “there is” as in the statements like “it is raining” or “it’s a nice day” remain at the “absolutely-impersonal” level.

But when we come to human beings, we move beyond the mere “recognition of things.” It is in this experience that the human subject realizes that it cannot be “sufficient unto itself.”

It is the meeting with the other person that facilitates “the first exiting from self.” In experiencing the 'other,' I can, so to speak, let go of myself. The other human person is, therefore, the threshold to transcendence. In the encounter with them I can pass through to the 'Other.' The Other is in our midst and is as proximate to us as our neighbor.

The epiphany of the human face, in the Levinasian perspective, actually “constitutes a penetration of the crust” of the human being who is “preoccupied with itself.”

Our responsibility before others in putting them first is a “disinterested” love, which is a new kind of holiness. This type of vocation of holiness, according to Levinas, is what essentially defines the human. He observes how it is in this way that “the human has pierced through imperturbable being; even if no social organization, nor any institution can… ensure, or even produce saintliness.”

Priority of the 'other': saintliness

In an interview given in 1987, Levinas explains how “the encounter with the other is the great event,” and this cannot be reduced to the mere acquisition of knowledge. It might be the case that I can never totally understand the 'other,' but “the responsibility for him, where language is born… overflows knowing” as such. (Unforeseen History)

In answer to the question, “What is ethics?” Levinas answered, “it is the recognition of ‘saintliness.’” He outlines how the fundamental preoccupation of each individual being is its own being. When it comes to the world of plants and animals, “all living things hang onto their lives.” In each case it is all about “the struggle for survival.”

But when you come to the encounter with the human, you have the “possible advent of an ontological absurdity.” The experience, he says, is that “the concern for the other is greater than the concern for oneself. This is what I call ‘saintliness.’ Our humanity consists in being able to recognize the priority of the other.”

This is awakened before the ‘face’ of the 'other.' So, Levinas believes that it is in putting the other person first “that God comes to mind.” Human existence lived in terms of this “priority” of the “other” is “transcendence.” It essentially means we escape or exit ourselves.

There is, Levinas says, a deep need to “to come out of being” and not remain “cramped inside a tight suffocating circle.” (On Escape) He holds that when he uses the term “face,” he means the 'other.'

Indeed, when we think of the experiences of the international pandemic, when we all had to wear masks, we can easily understand what Levinas has in mind. The “face” is what is behind the mask because it is “behind the façade and under the countenance that each person gives himself.” The challenge was that we could not even see each other face to face, which ends up deconstructing who we are as human persons.

The wisdom of love

Levinas, when asked “what is philosophy?” explains that traditionally it is understood as the “love of wisdom,” but he sees it as the “wisdom of love.” We can at times run the risk of being intoxicated by “the rhythm of words and the generalities they express.” So, there is a continual need and challenge to “be awakened” by the 'other.'

It is in this way that we can open ourselves up to “the distinctiveness of the unique in the real,” which we discover in the uniqueness of other persons. He sees philosophy as being a kind of “insomnia,” that is, being continually awake to who the “other” really is.

Levinas describes how “transcendence is what faces us. A face breaks up the system.” In masking up during the health crisis, we missed the experience of “the face which looks at me affirming me.” It is when we are “face to face” that we can “no longer negate the other.” He says we cannot “escape the face of the neighbor” (Collected Philosophical Papers, 167).

Our awakening to this reality can be described as a “shudder of the incarnation through which giving takes on meaning… in which a subject becomes a heart.”

In Levinas’s perspective, it is in living out this priority that we become and discover who we are as human beings.