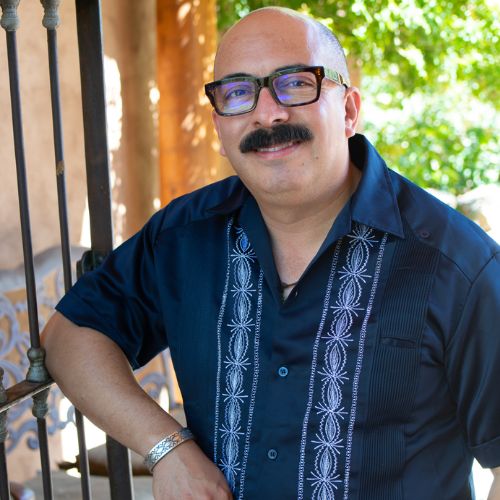

A mexican posada

Last year, I attended the unveiling of a relic of a Catholic saint at the Most Holy Redeemer Church in Detroit. The church was packed, with people seated and standing everywhere. The first-class relic belonged to San José Sánchez del Río, known as Joselito. He was fourteen years old when he died as a martyr during the Cristero War in Mexico, a large-scale conflict between the Catholic Church and the Mexican state from 1926-29. Joselito wanted to fight during the War, but because of his age was only allowed to serve as the flag-bearer for a troop of Catholic rebels. He was captured, tortured, and eventually killed on February 10, 1928.

Joselito is one of many saints whose devotions have crossed over into the U.S., illustrating how the religious Catholic landscape in the U.S. has changed due to migration from Latino America.

In the August 2024 issue of Maryknoll Magazine, Marietha Góngora reported that currently 99% of all U.S. dioceses, and around a third of all parishes, offer at least one Sunday Mass in Spanish. Additionally, a 2025 report by the Pew Research Center states that “today, 36% of all Catholic adults in the United States are Hispanic, up from 29% in 2007.” Moreover, in 2024, the National Encuentro of Hispanic/Latino Ministry research team, part of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), declared that “from 1990 to 2021, the U.S. Hispanic/Latino Catholic population increased by about 14.6 million, while the overall U.S. Catholic population only increased by about 5.8 million, indicating a net loss of 8.8 million non-Hispanic Catholics.”

In other words, during this period, the growth of the U.S. Hispanic/Latino Catholic population was approximately 252%. Additionally, according to the USCCB, “nearly 50% of Catholic children under the age of 17 and born in the United States are Hispanic/Latino.” This marks a significant transformation within the religious institution, particularly considering that most Latino Catholics are under thirty years old.

These figures reflect a broader national trend of a significant demographic shift. It is important to remember that the distribution and location of Latino Catholics vary greatly between regions, dioceses, and even individual parishes. Furthermore, this transformation is no longer confined to the American Southwest, a traditional Latino region. It has now spread to small towns and middle America, regions deeply affected by the loss of industrial jobs and the migration of young people moving into big cities.

Currently 99% of all U.S. dioceses, and around a third of all parishes, offer at least one Sunday mass in Spanish.

One important point to highlight is that Latino Catholics are not a new phenomenon. On the contrary, they have been present on the continent from very early times, even before the formation of the U.S. as we understand it today. The oldest European-established and continuously inhabited city in the U.S. is located in Florida. San Agustín was founded in 1565 by the Spanish Crown and served as an important hub of commerce between the Caribbean and colonial New Spain. This city predates both Jamestown (1607) and Santa Fe (1610). The region of New Orleans also has long-standing economic and cultural ties to Caribbean colonies, dating back to before this territory became part of the U.S. Our current Pope Leo XIV, an American, has a family that shares this historical trajectory.

A very important development occurred as a consequence of the Mexican-American War (1846-48), when Mexico was forced to cede 55% of its territory to the U.S. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), signed to end the conflict, solidified this massive territorial expansion for our nation. It also granted U.S. citizenship to Mexican nationals who chose to remain in the newly-acquired territories. The treaty explicitly protected their Catholic faith by ratifying “the free exercise of their religion without restriction.” Let’s also not forget about Puerto Rico, a territory that is part of the U.S. and has a predominantly Catholic population. In many ways, Latino Catholics are an intrinsic element of what we now understand as the United States.

Latino Catholic migration has been a key factor in shaping the religious landscape of America in recent years. The Pew Report referenced earlier indicates that today, “among Hispanic Catholics, 58% were born outside the U.S., and 22% were born in the U.S. to at least one immigrant parent.” These trends present a unique challenge for the mainstream Catholic Church, which is already grappling with a decline in vocations to the priesthood.

The challenge goes beyond simply offering services in Spanish; they are cultural and devotional in nature. For example, as indicated in the Pew Report, while only 22% of white Catholics claim to pray the rosary, 37% of Latino Catholics report doing so. Additionally, 63% of Latino Catholics consider devotion to the Virgin Mary to be essential to their faith, compared to only 42% of white Catholics. These numbers may seem surprising given the central roles of some of these elements, but they highlight the deep dissonances that exist within people’s faith, practices, and beliefs. At the same time, many Latino Catholics may identify as culturally Catholic, but not as doctrinally devout.

Here are two examples that may help us understand the spectrum of Latino Catholic experiences. I have a faculty friend in California who grew up in a very Catholic family. He was baptized, but no longer identifies as Catholic. In fact, he’s quite clear about his opposition to many aspects of the Catholic Church as an institution. However, if you visit his office, you will see a large image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and his home is filled with Catholic religious figurines and references. For him, and for many Latina feminists, the Virgin of Guadalupe is primarily a cultural icon, a symbol of pride and resistance. In this sense, I believe that Mary’s love for people has allowed her to remain a meaningful figure for many Latinos, even when they no longer feel welcomed or connected to the institution that holds her son’s memory.

Another example happened last winter, when I was visiting my mom, who lives in a predominantly Mexican neighborhood in the American Southwest. One afternoon, as we were driving home, we noticed that a Catholic church in the neighborhood had organized posadas for Christmas. A posada is a traditional Latin American celebration that reenacts Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter in Bethlehem before the birth of Jesus. Without hesitation, we parked the car and joined the people as they walked, prayed, and sang Christmas carols in Spanish. A posada is a religious event, but it also serves other functions, primarily strengthening community bonds. It promotes trust, solidarity, and mutual care among neighbors, as people are invited to socialize afterwards in someone’s home. We didn’t know these neighbors personally, but through the posada, a sense of religious affinity and trust was established. Now, when we walk by their homes, we say hello and stop to chat. We are no longer strangers.

As we see, the relevance and attachment to specific Catholic cultural and devotional practices vary among individuals, families, and different national and cultural groups. We know that parishes (and the many collective rituals and events they host) serve a crucial function beyond solely religious purposes. This is especially true for displaced communities or those experiencing distress. In other words, parishes function as cultural and civic spaces where the secular and the religious are often intertwined, not always clearly differentiated, but deeply interconnected.

Latinos make up nearly 40% of all Catholics, yet as of 2024, only about 10% of active bishops in the U.S. are Latino.

Despite being the largest religious faith among Latinos in the U.S., the number of Catholics within this community is consistently declining. Many are shifting to other faiths or becoming unaffiliated with any religious group. A 2023 Pew Research Center report illustrates that within the Latino population in the U.S., the percentage of Latino Catholics dropped by twenty-four points, from 67% to 43% from 2010 to 2022. “By contrast, the share of Latinos who identify as Protestants—including evangelical Protestants—has been relatively stable, while the percentage who are religiously unaffiliated has grown substantially over the same period.” This trend is especially pronounced when examining different age groups. For example, nearly half (49%) of Latinos aged 18-29 identify as religiously unaffiliated. Additionally, those born in the U.S. are more likely to be unaffiliated than recent migrants. This pattern is also reflected in the decline in Latino priest ordinations which, according to a Georgetown University report, decreased from an all-time high of 22% of all ordinations in 2022, to 16% in 2023, and 18% last year. It may still be early to determine the permanence of this trend, but the data suggests a significant shift.

The factors driving the decline in Catholic faith affiliation and participation among Latinos are complex and involve many social dynamics. Many Latino migrants have felt misunderstood, judged, and discriminated against in their parishes. They’ve also lost social networks that previously linked them to their family’s hometown parishes as they migrated to the U.S. In many parts of Latin America, Catholic priests and parishes traditionally hold significant social and governance roles. These religious and cultural practices are often less prominent in many settings in the U.S.

As a result, many Latino Catholics are turning to other faiths because they find in these communities a narrative and connection with the transcendental that resonate with their experiences. These faith communities often provide a space where they can confront everyday struggles with dignity, love, and care.

In addition, Latino Catholics are underrepresented in the decision-making leadership of the Catholic Church in the U.S. relative to their population size and demographic significance. As mentioned earlier, Latinos make up nearly 40% of all Catholics, yet as of 2024, only about 10% of active bishops in the U.S. are Latino, the Georgetown study indicates. The USCCB has made efforts to address the broader structural and historical barriers within the institution. As part of these efforts, the bishops recently (June 16, 2023) approved a National Pastoral Plan for Hispanic/Latino Ministry, which outlines a path of action for the next decade. The plan includes pastoral priorities, initiatives, and guidelines. This issue is both urgent and highly relevant.

Certainly, there is a lot of work that needs to be done. But we know that God is an active actor in history, and there is a beautiful plan for humanity and our nation. I typically teach a lecture within two of my courses titled “When Lupe Moves North,” which is an analysis of the Virgin of Guadalupe, its devotional significance, and how its representation and meaning have evolved within Latino communities in the U.S.

There are two images I particularly love. The first is by Chicana artist Esther Hernández, titled La Virgen de las Calles (Our Lady of the Streets). It depicts the Virgin of Guadalupe as a female street flower vendor. As the artist explains, it “pays tribute to the dignity, strength, and perseverance of immigrant women as they strive for a better life for themselves and their families.” In this image, Mary appears old and tired, but she maintains a courageous and defiant attitude. I keep a copy beside my bed, as a reminder that Mary, in her role as a layperson, is sometimes inconspicuous.

The other piece is by artist Tony Ortega, called La Marcha de Lupe Liberty. In this artwork, Ortega has “digitally combined images of the Statue of Liberty and Our Lady of Guadalupe.” In this scene, the Virgin is accompanying a group of Latinos during a march, holding American flags. I love this image because it emphasizes that Mary is always present, walking with us toward a world that reflects the prayer: “May your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.”