Photo by Ben Duchac on Unsplash

Pope Francis’ idea of a “mysticism of encounter” has a wealth of implications. Not only does it link communion with God to the concreteness of daily life and interpersonal relations, it also sheds new light on the Gospel’s social dimension: the order of our home (oikos) and city (polis), economics and politics, care for our earthly home, and scientific and technological progress, are all inseparable realities from that of the coming of the kingdom.

Among the principal ideas inspiring the thought and writing of Pope Francis, paragraph 272 of Evangelii Gaudium stands out. It contains an invitation to live in relationship with others in such a way as to “learn something new about God.”

It’s a rich and provocative statement. This is because the pope considers our interiority to be the place where heart and mind immerse themselves in God. He invites us to grow inwardly, to expand our borders, widen our horizons, and extend hospitality to others.

To “enlarge our inner life” almost seems a contradiction in terms. But, it refers to a specific kind of interiority: that evangelical interiority that is a fruit of the coming of the kingdom and generated by the resurrection of Jesus. Pope Francis describes it in this way:

“When we live out a spirituality of drawing nearer to others and seeking their welfare, our hearts are opened wide to the Lord’s greatest and most beautiful gifts. Whenever we encounter another person in love, we learn something new about God. Whenever our eyes are opened to acknowledge the other, we grow in the light of faith and knowledge of God” (272).

Pope Francis continues to emphasize and reiterate that spirituality is not an individual’s own isolated exercise of growing in one’s interior life. Rather, it’s an experience of “the we,” generated by the risen Christ through encounters with others.

Such a spirituality is a marked shift away from current practices, which are also very different from those of early times, and signifies a marked shift and renewed focus toward practices described in the Gospel and in the great tradition of the Church.

It is that space where our relationship with God happens as a result of our relationship, in Jesus, with others in this world. In this way, we can rightly say that our interiority “enlarges”—onto others—and takes on the dimension of a meeting place with God, and in him, with each individual and with all.

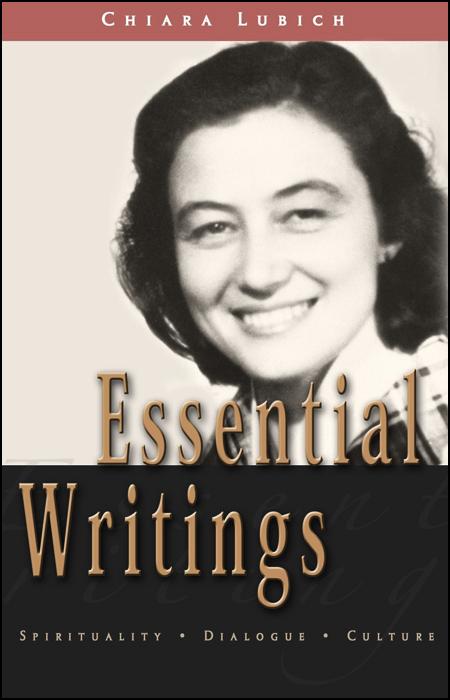

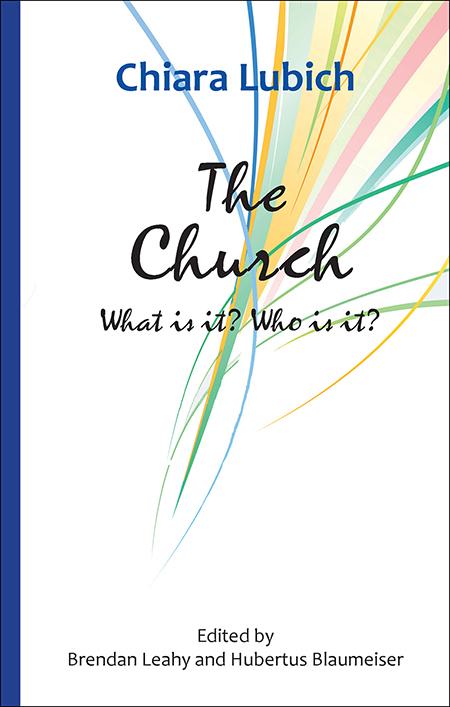

So, too, the “interior castle” of Teresa of Avila, markedly interior in nature, is strengthened rather than diminished by its opening out to the ‘exterior castle’ as described by Chiara Lubich (Reciprocity between the “interior castle” of Teresa of Avila and the “exterior castle”—bringing the presence of God into society—was mentioned by Chiara as early as 1949) Even if we are not always fully aware of it, the God that in Jesus, through the Spirit, lives in me and in each one, is also alive wherever two or more are gathered in his name (see Mt 18:20). Thus, our meeting with one another becomes an experience of ‘mystical fraternity’ (92).

The Gospel alternative for society today

The experience of “we” is clearly a spirituality insofar as we speak of a personal experience of God, of a God present wherever Jesus is alive and present today. He is present in the living flesh of the other and among the faithful. From this we see the immense implications of the ‘realism of the social aspect of the Gospel’ 88).

Pope Francis, quoting the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, says that “God, in Christ, redeems not only the individual person, but also the social relations existing between people” (52).

To believe that the Holy Spirit is at work in everyone means realizing that God seeks to enter into every human situation and all social bonds … Evangelization is meant to cooperate with this liberating work of the Spirit. The very mystery of the Trinity reminds us that we have been created in the image of that divine communion, and so we cannot achieve fulfilment or salvation purely by our own efforts. From the heart of the Gospel we see the profound connection between evangelization and human advancement, which must necessarily find expression and develop in every work of evangelization (178).

Spirituality, as an experience of God through the divine reality of Christ, does not tear us away from the concrete events of human history. Rather, it is the channel by which the blood of God flows through the flesh of this world.

The order of our homes (oikos) and our cities (polis), economics and politics, care for our earthly home and all matters of scientific and technological activity are not totally separate from the coming of the kingdom.

Yet, because of their undeniable autonomy, they are the places and channels by which the history of humankind, and the entire cosmos, unfold. In front of contrasting temptations to flee from today’s world (fuga mundi) or to instead adopt a theocratic Christianity, what emerges is another alternative for society: a societal alternative in which the Gospel becomes the leaven, salt and light, that gives form, flavor, and direction to human history.

From this, we better grasp the truth, and the practical and social significance, of a passage from Gaudium et Spes which, at first glance appears primarily spiritual and ethical in nature:

“The new command of love was the basic law of human perfection and hence of the world’s transformation. To those, therefore, who believe in divine love, [Jesus] gives assurance that the way of love lies open to men [and women] and that the effort to establish a universal brotherhood is not a hopeless one.” (38) …

Or, in the words of Pope Francis, to be “contemplatives of the Word and of the people of God” is to see two faces of the same medallion (EG 154).

First published in Ekklesia, January-March 2019